or

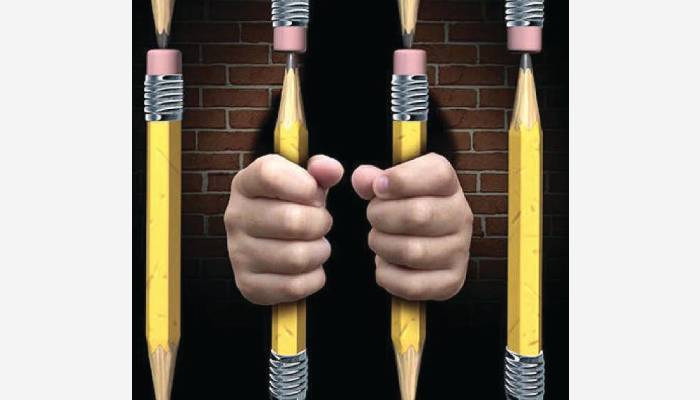

This question will need to be addressed sooner and with alarming frequency after the Juvenile Justice Bill, 2014 is enacted. While the Bill has received assent in both the houses of Parliament, it still hangs in the balance as far as public opinion, and indeed, the test of constitutional validity is concerned.

Much has been said about the occurrence of the night of December 16, 2012 – a gang rape of such intensity and ferocity that it left its mark in mainstream consciousness across the world. Ironically, the most active perpetrator of the crime was, at that point of time, a juvenile – a person who was yet to complete 18 years of age. And, when society encounters such incidences involving juveniles – persons who are accorded the highest level of care and protection (at least in theory)– it flounders and is usually unable to grapple with the social, moral, ethical and legal dilemma that the situation poses.

India struggles with a bleak record of protecting its young ones. Ranked at 149 with a score of 5.42, below even war-torn Palestine (ranked 137 with a score of 6.55) and Iraq (ranked at 140 with score of 6.40) in the context of the Realization of Child Rights’ Index, India clearly has a long way to go. Considering the fact that over 40% of India’s population is below the age of 18 years, it is critical to know how we as society and governments our children.

The soon-to-be-replaced Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000, (“the Old Law”) is the primary legislation that governs the interaction between juveniles and the legal mechanism in the country. It defines a juvenile as a person who has not completed eighteen years of age. After describing its temporal jurisdiction, the Old Act elaborates upon a regulatory framework to provide special care and protection that enables rehabilitation of juveniles who fall foul of the law.

In India, where matters of child rearing, custody, marriage and inheritance are still governed by an intricate fabric of personal religious laws, this benchmark age itself has been a cause of great debate in legislative, social and even some judicial battles. So much so that a person is often considered adult enough to marry and give consent to such marriage at the onset of puberty although he or she may still very much be a juvenile under the Old Act. This inconsistency in the legal protection afforded to children automatically questions the efficacy of a central law like the Old Law in providing comprehensive care to juveniles. To address this issue, therefore, it was necessary to usher in legislative reform that focused on the welfare of the child and made the care of the child central to the system.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Bill, 2014, (“the New Law”) thus, was a golden opportunity to plug gaping loopholes such as this one. Unfortunately, it has ended up being a knee-jerk reaction to a single incident. The New Law provides for juveniles between the ages of 16 and 18 years to be tried as adults in certain cases when they are accused of the commission of heinous crimes.

So, when is a child not a child? As we address the need to rein in newer crimes and negative behavior patterns that are emerging in our day and time, it is imperative that we understand how our children are growing up. In the face of perennial access to information and constant connectivity, children are growing up faster than they can mentally or emotionally keep pace with. “Our society is compressing childhood more and more and are under tremendous pressure to ‘be mature’ and to ‘grow up’ when they have not had the chance to develop emotional maturity.” While this sentiment is reflected across First World economies, India is no stranger to this phenomenon. Its implications reflect on the social fabric of a country where economic disparity, religious animosity and other divisive trends have already earmarked large sections of the population as especially vulnerable. In such a situation, it becomes compulsory for the law to take into account factors that affect juvenility – and the behavior of a juvenile under scrutiny – while making a framework to provide for the care and protection of minors. The New Law, sadly, does not legislate the need to evaluate such factors, although a catena of judgments in the area of juvenile justice based on the Old Law do touch upon the topic.

Perhaps the most obvious pitfall of treating children like adults is the loss of trust in the innocence of childhood and the faith in the need to protect children. Apart from treating juveniles as adults in certain situations, the new law also provides for trial of crimes committed during minority as equal to crimes committed during majority in a situation where a juvenile between the age of sixteen and eighteen years of age is suspected of the commission of a heinous crime but is apprehended after he or she has attained majority.

This means that the legal process one is subjected to and as the punishment one is awarded depend not only on the gravity of the offence but also on the time at which one is apprehended. Effectively, this will violate the Constitutional right to be treated equally by the law, especially in cases when two juveniles between the stipulated ages are accused of the commission of a heinous crime but one is apprehended before he or she completes the age of eighteen years and the other afterwards.

It is ill-thought out provisions such as these and the implication that they can potentially have that renders the New Law a retrograde step in legislative resolution to the problem of juvenile delinquency in India.

Crime leaves an indelible mark on its victims and when a crime involves juveniles, whether they are active participants in perpetuating it or not, they are all essentially victims. This bitter truth has been underscored time and again, whether we look at the problem of child soldiers or trafficking of children. When a country fails to address the reason of the cause of violence involving children and merely seeks to address the symptoms, it is indeed playing a dangerous game with its future. The legislatures had the opportunity to bring in substantive legislative provisions to enable reformative and restorative practices to address juvenile delinquency. What it does, however, is merely provide an institutional structure without defining the manner in which the core legal responsibility of social reintegration is to be achieved. While criminal law and personal matters including infants and minors are within the purview of the Central as well as the State Governments, surely it behoves our body politic to have a cohesive vision for our children that provides the highest level of care and protection that understands and addresses the needs of children. By leaving a wide scope for interpretation and variation in enactments at the State level, the new legislation yet again fails our future generations from an equal standing before the law.

To conclude, every successive legislation on the subject of the care of children must be a step towards making a better world for them to grow up in and this process begins by ensuring that no child is the child of a lesser god. At this fundamental level, the New Law must prove itself on the touchstone of constitutional validity and more importantly, on the real concerns of securing our future generations.

The author is, advocate, public law and policy

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved