or

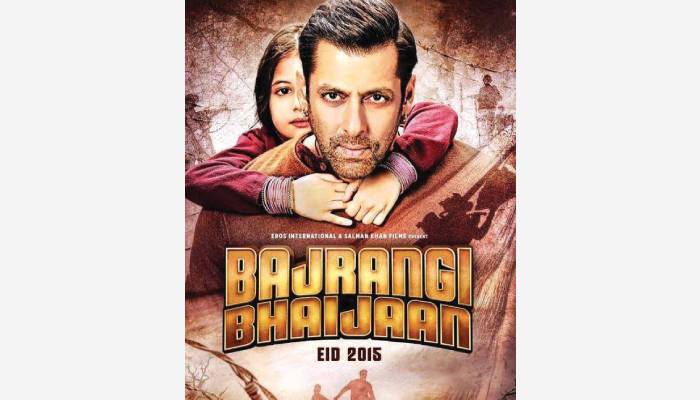

After many positive reviews and chart topping cinema runs, Bajrangi Bhaijaan(“the Film”) can safely be called a successful Hindi Film. However, like every second Indian film, Bajrangi Bhaijaan is not free from controversy. This one is called ‘Chand Nawab’.

Chand Nawab is a news reporter from Pakistan. In 2008/2009, a video of Mr. Nawab attempting to present a news bite, about people travelling out of Karachi to spend Eid with their loved ones, went viral on the internet. This news bite was being presented from a busy railway station, which, combined with a distracted Mr. Nawab, and perfectly timed comical interruptions made for a hilarious twominute video, which was not only watched by many on the internet but was also downloaded and circulated through emails, messages etc.

This viral video has been recreated entirely in the Film. The character in this recreated scene, portrayed by Mr. Nawazuddin Siddiqui, is also a Pakistani news reporter named Chand Nawab. Pertinently, it is not only the scene of a distracted news reporter at a busy railway station which has been recreated but even the dialogues are borrowed from the viral video. After the release of the Film, Mr. Nawab has requested for compensation for using a character inspired by him and recreation of the said video.

The Supreme Court in R.R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu, (JT1994(6)SC514) has held the violation of ‘Personality Rights’ to mean the use of a person’s likeness or name, without consent, for advertising or non-advertising purposes. Violation of Publicity Rights, a term often used interchangeably with Personality Rights, or which may be considered a narrower right, arises when such unauthorised use is for commercial gain. The Delhi High Court in Titan Industries v. Ramkumar Jewellers 2012(50)PTC486(Del), quoting Healan Laboratories v. Topps Chewing Gum(202F.2d866),has rightly opined that a right in one’s personality is not merely a right arising from bruised feelings through public exposure of… likeness. An action for violation of personality right under the tort of misappropriation may also lie, especially if an individual’s persona is appropriated for commercial gain, as was the case in D.M. Entertainment v. Baby Gift House, CS(OS)893/2002.

Interestingly, this commercial right is usually associated with celebrities who are well-known in the field of cinema, music, sports, etc. and logically so. In fact, while allowing ‘Rajnikanth’s’ plea for injunction against the film ‘Main HoonRajnikanth’, the Madras High Court in Shivaji Rao Gaikwad v. Varsha Productions, (2015(62)PTC351(Mad)) opined that the personality right vests on those persons, who have attained the status of celebrity. Thus, one wonders, whether Mr.Nawab has any right to claim compensation for the use of his personality, likeness, etc. at all?

One’s rights in one’s persona, pictures, likeness, etc. can be considered akin to a property right. All “persons” enjoy equal rights in their own property irrespective of their “celebrity” status. Even otherwise, it was held in ICC Development (International) v. Arvee Enterprises, (2003(26) PTC245Del) and in the R.R. Rajagopal case that Personality Rights and the right to commercially exploit one’s persona are facets of the right to privacy guaranteed in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Article 21 right is applicable uniformly to all “persons” and no person can be deprived of this right except in accordance with the procedure established by law. Thus, Mr. Nawab’s right in his own personality traits should not be affected by his status as a celebrity, or the lack of it.

Recently in the U.S.A., the use of the likeness of Facebook’s non-celebrity/ordinary members in connection with Sponsored Stories has brought to light the importance of guaranteeing personality / publicity rights to allin a time when internet and social media have thinned the lines of privacy. Although the litigation was settled outside court, Forbes.com reported that Facebook paid 614,994 of its non-celebrity members for the use of their likeness.

Nevertheless, the Titan case defined ‘celebrity’ to mean a famous or a well-known person. A “celebrity” is merely a person who “many” people talk about or know about. As mentioned, the video had gone viral in 2008/09and was widely circulated. Further, Mr. Nawab has been talked about in the media since the release of the film. Mr. Nawab, today, is a known and talked about person, in India and in Pakistan and thus, fits in the broad definition of “celebrity” so as to have protectable publicity rights as also rights under the broader frame of personality rights.

In a recent interview with NDTV, the film makers confirmed that the impugned scene is an exact replication of Mr. Nawab’s viral video. Thus, the present facts qualify the two-step test enunciated in the D.M. Entertainment case. Firstly, Mr. Nawab is obviously identifiable from the use in the Film. Secondly, the use is sufficient, adequate or substantial to identify that the film-makers have appropriated the persona or some of its essential attributes.

It would be untenable for one to argue that the viral video was incorporated in the Film for no intended commercial gain. Regardless, as per the R.R. Rajagopal case, the purpose of use in determining the violation of personality rights is not relevant, as long as the use of a person’s likeness is unauthorised. It is trite law that a person may not be deprived of his property without adequate compensation. Therefore, unless Mr. Nawab had granted permission to the film makers to use attributes of his personality without compensation, he is likely to succeed in raising an issue of infringement of his publicity and personality rights.

Savni D. Endlaw, Associate Partner, is a part of Saikrishna & Associates’ litigation and dispute resolution team. She represents some of the top tech companies (social media, e-commerce, aggregators etc.), OTT service providers, broadcasters, authors, and publishers with focussed advice on technology laws, media and entertainment laws, cross border IP issues, sports law, intermediary liability, privacy laws, and defamation laws.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved