or

Insolvency proceedings were earlier governed by the SARFESI Act, 2002, the Recovery of Debts due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993, Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Act, 1985, Corporate and Strategic Debt Restructuring under RBI Guidelines.

In India, the process of resolving insolvency has been very time–consuming as compared to any other progressive economy around the world. The erstwhile laws were mainly designed for enforcement and were not effective in revival of the sick companies. Also, the prescribed revival of sick companies under the same management was often ineffective in nature and there was no time bound process due to which moratorium often continued for the indefinite period. There are always a multitude of litigations pending for debt recovery. India seems to be lacking an appropriate legal framework to deal with Insolvency as per global standard. As per the World Bank data, the average time taken to resolve insolvency in India is 4.3 years, which is way higher when compared to United Kingdom (1 year), United States of America (1.5 years) and South Africa (2 years).

The aim to overcome the shortcomings of Indian insolvency laws has led to the enactment of the Insolvency Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (The Code).

The Code has introduced the adjudicating authorities having an exclusive jurisdiction to deal with insolvency matters i.e. NCLT/ NCLAT, DRT/ DRAT etc.

The Code offers uniform and comprehensive insolvency legislation encompassing all companies, partnership firms, limited liability partnership firms, individuals and any other body specified by the Central Government other than financial firms.

The Code seeks to consolidate the existing framework by repealing Presidency Towns Insolvency Act, 1909, and Provincial Insolvency Act, 1920, as well as amending 11 other legislations

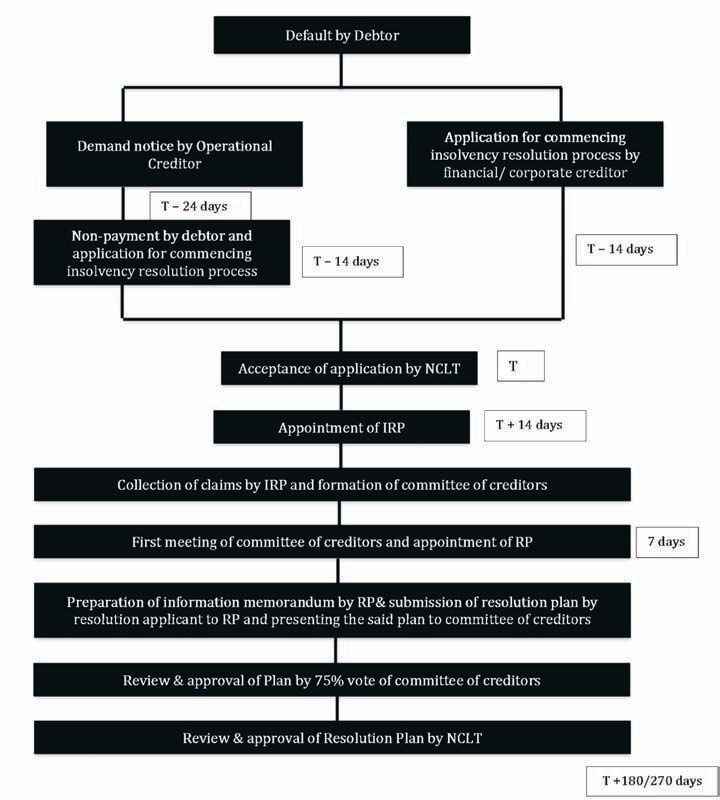

To meet the objectives of timeliness and value maximization, the Code proposes a new institutional set-up comprising four critical pillars:

IRP will end under the following circumstances:

The Code’s journey so far has been no different from other similar legislations and is still looking for consistency and clarity.

For example, in relation to the term ‘dispute’ as defined under Section 5 of the Code, NCLT has held that use of the term “includes” as used in the definition clause of ‘dispute’ has to be read as “means”. Thus an inclusive non-exhaustive definition has turned turtle, thereby saying that there should be an existing suit or arbitration only.

Contradicting views in separate proceedings, even by different benches is also not helping the cause of consistency. NCLT has taken different views in two separate cases by merely citing the reason that the view in the earlier case was taken during the “formative days”.

Recently the NCLT allowed Insolvency resolution proceedings despite pendency (Vasan’s case) of a winding up petition taking a view that the same could not be bar under the Code for initiating the corporate insolvency resolution process, as the High Court had not passed any order for winding up and no official liquidator had been appointed.

In another recent development, the NCLAT refused to entertain India’s largest private Lender on a default application against Starlog Enterprises. While the lenders cannot take the due process for granted, the confusion and lack of consistency is likely to raise questions on the very objective and rationale behind the Code in time to come. An effective ‘ease to do business’ regime requires a robust Insolvency ecosystem to address challenges of an emerging economy like India. For this, all eyes remain on NCLT.

Dr. Manoj Kumar is the Founder of Hammurabi & Solomon & Visiting fellow with Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved