or

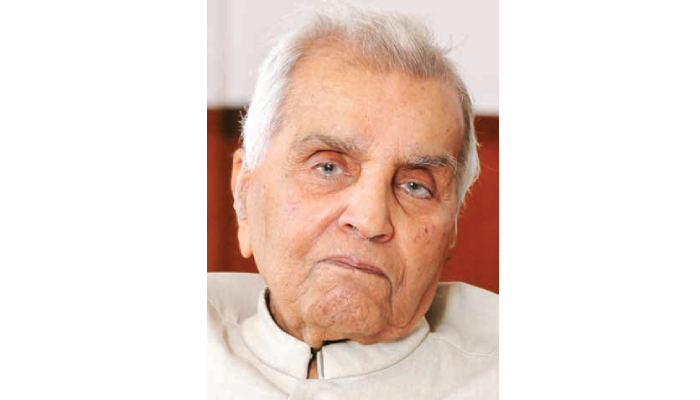

Justice Rajindar Sachar was an Indian lawyer and a former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court. He was a member of United Nations Sub- Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and also served as a counsel for the People’s Union for Civil Liberties.

Sachar chaired the Sachar Committee, constituted by the Government of India, which submitted a report on the social, economic and educational status of Muslims in India.

Rajindar Sachar was born on 22 December 1923. He was a practicing Hindu. His father was Bhim Sen Sachar. His grandfather was a well-known criminal lawyer in Lahore. Sachar attended D.A.V. High School in Lahore and then went on to Government College Lahore and Law College, Lahore.

On 22 April 1952, Sachar enrolled as an advocate at Shimla. On 8 December 1960, he became an advocate in the Supreme Court of India, engaging in a wide variety of cases concerning civil, criminal and revenue issues. In 1963 a breakaway group of legislators left the Congress party and formed the independent “Prajatantra Party”. Sachar helped this group prepare memoranda levelling charges of corruption and maladministration against Pratap Singh Kairon, Chief Minister of the Indian state of Punjab. Justice Sudhi Ranjan Das was appointed to look into the charges, and in June 1964 found Kairon guilty on eight counts.

On 12 February 1970, Sachar was appointed Additional Judge of the Delhi High Court for a two-year term, and on 12 February 1972, he was reappointed for another two years. On 5 July 1972, he was appointed a permanent Judge of the High Court. He was acting chief justice of the Sikkim High court from 16 May 1975 until 10 May 1976, when he was made a judge in the Rajasthan High Court. The transfer from Sikkim to Rajasthan was made without Sachar’s consent during the Emergency (June 1975 – March 1977), when elections and civil liberties were suspended. Sachar was one of the judges who were transferred as a form of punishment and he refused to follow the bidding of the Emergency establishment. After the restoral of democracy, on 9 July 1977, he was transferred back to the Delhi High Court.

In June 1977, Justice Sachar was appointed by the government to chair a committee that reviewed the Companies Act and the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, submitting an encyclopedic report on the subject in August 1978. Sachar’s committee recommended a major overhaul of the corporate reporting system, and

particularly of the approach to reportingon social impacts. In May 1984, Sachar reviewed the Industrial Disputes Act, including the backlog of cases. His report was scathing.

In November 1984, Justice Sachar issued notice to the police on a writ petition filed by Public Union for Democratic Rights on the basis of evidence collected from 1984 Sikh riot victims, asking FIRs to be registered against leaders named in affidavits of victims. However, in the next hearing the case was removed from the Court of Mr. Sachar and brought before two other Judges, who impressed petitioners to withdraw their petition in the national interest, which they declined, then dismissed the petition. Justice Sachar declared much later that his memory is still haunted by the reminiscence of not being able to get FIR registered in these cases.

Sachar was Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court from 6 August 1985 until his retirement on 22 December 1985.

Sachar, who had formerly been a United Nations special rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, headed a mission that investigated housing rights in Kenya for the Housing and Land Rights Committee of the Habitat International Coalition. In its report issued in March 2000, the mission found that the Kenyan government had failed to meet its international obligations regarding protection of its citizens’ housing rights. The report described misallocation of public land, evictions and land-grabbing by corrupt politicians and bureaucrats. Rajindra Sachar participated with

retired Justices Hosbet Suresh and Siraj Mehfuz Daud in an investigation by the Indian People’s Human Rights Tribunal into a massive slum clearance drive in Mumbai, which had the ostensible purpose of preserving the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. The demolitions on 22–23 January 2000 had been undertaken despite a notification from the state government to stay demolitions until September. The people had not been allowed to take the remains of their homes, which had been burnt. Sachar described the scene as “Barbaric, savage. It’s as if a bomb has fallen here”. In August 2000 the judges, joined by former Supreme Court judge V. R. Krishna Iyer, held a two-day hearing into the clearances in which about 60,000 people had been evicted. The inquiry covered both legal aspects of the clearances and the human impact.

In March 2005, Justice Rajinder Sachar was appointed to a committee to study the condition of the Muslim community in India and to prepare a comprehensive report on their social, economic and educational status. On 17 November 2006 he presented the report, entitled “Report on Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India”, to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The report showed the growing social and economic insecurity that had been imposed on Muslims since independence sixty years earlier. It found that the Muslim population, estimated at over 138 million in 2001, were underrepresented in the civil service, police, military and in politics. Muslims were more likely to be poor, illiterate, unhealthy and to have trouble with the law than other Indians. Muslims were accused of being against the Indian state, of being terrorists, and politicians who tried to help them risked being accused of “appeasing” them.

The Sachar Committee

recommendations aimed to promote inclusion of the diverse communities in India and their equal treatment. It emphasized initiatives that were general rather than specific to any one community. It was a landmark in the debate on the Muslim question in India. The speed of implementation would naturally depend on political factors including the extent of backlash from Hindutva groups. The Sachar Committee Report recommended setting up an institutional structure for an Equal Opportunity Commission. An expert group was established that presented a report, including a draft bill to establish such a commission, in February 2008. There was opposition. Thus, a speaker at a seminar in April 2008 sponsored by a group called “Bharatiya Vichar Manch” described the report as unconstitutional, saying “It should be rejected completely. It is on communal lines and will divide the country. It is a result of vote bank politics”.

In 2003, as counsel for the Centre for Public Interest Litigation (CPIL), Sachar and Prashant Bhushan challenged the government’s plans to privatise Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. CPIL said that the only way to disinvest in the companies would be to repeal or amend the Acts by which they were nationalised in the 1970s. In December 2009 it was reported that Sachar was being proposed as Governor of West Bengal to replace Gopalkrishna Gandhi, whose term had expired. In the event, Devanand Konwar was appointed acting governor.

Sachar was suffering from heart ailments. In April 2018, he was admitted to the Fortis Hospital in New Delhi. He passed away during the course of his treatment on 20 April, midnight.w

The LW Bureau is a seasoned mix of legal correspondents, authors and analysts who bring together a very well researched set of articles for your mighty readership. These articles are not necessarily the views of the Bureau itself but prove to be thought provoking and lead to discussions amongst all of us. Have an interesting read through.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved