or

How often do we come across the blanket term “All Rights Reserved” while browsing a new website/mobile application? But the real question is, can simply adding a footer truly reserve all your rights?

The general misnomer of the market players is that the look and feel of their website/mobile application being a combination of literary and artistic work is automatically protected under the Copyright Law (“Copyright”), or the infamous “All Rights Reserved” embossment. But the cryptic fact that most of the market players are unaware about is that they actually need a registered design to protect their Graphical User Interface (“GUI”) when it comes to the commercial climate.

Companies invest heavily on GUI because it is an essential component of how a website or mobile application looks and feels, and has in turn become a key differentiator in the market. GUIs have become one of the most dynamically expanding expression of intellectual property (“IP”), and are currently protected under copyright, as well as Design Law (“Design”) in India.

While at the outset this might seem like an ideal dual IP protection under both the statutes, but the lines get blurry when one realises that an IP can only be protected either as a design or a copyright, and not parallelly. So where does one actually draw the line between design and copyright?

It is a complicated situation within the creative space, and all the market players are grappling with this conundrum. In lieu of the same, this note explores the enigma behind dual IP protection of GUIs.

Countries with a robust technology industry, such as the US, Japan, South Korea, and EU, have moved on from providing copyright over GUIs in favour of a more benevolent design protection approach.

Around twenty countries, namelyArgentina, Brazil, China, Croatia, England & Wales, the European Union (as an entity separate from its member states), France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Sweden, Ukraine and the US, explicitly protect GUI as design as per a recently conducted ICC survey. Given that the primary purpose of a GUI is its aesthetic appeal, design protection comes in as a prudent choice.

Whereas, certain countries like Chile, Ecuador and the UAE do not allow design protection for GUIs, and in several other countries the protection of GUI still remains in grey area.

Prior to the development of GUIs, American courts established certain criteria over the scope of software programmes’ copyright protection. In the case of Whelan v. Jaslow (‘Whelan Test’), where a Dental Lab’s customer-service management programme was accused of violating copyright, the court expanded protection to include the program’s “structure, sequence, and organisation.” It held that non-literal elements i.e., figurative or creative elements which formed part of the expression, were protected by copyright. These components quickly gained notoriety as a program’s “concept and feel.”

However, the Whelan Test was disregarded in Computer Associates International v. Altai, Inc. (‘Altai Test’) and an abstraction-filtrationcomparison test was introduced, which first abstracted the expression from the idea before filtering out components that were either based on external factors, used for efficiency, or were taken from the public domain, such as colours and fundamental building blocks, before comparing the remaining components for infringement.

The extent of protection was significantly reduced as a result of the additional “filtration” that deleted various components that had previously enjoyed copyright.

Going forward in 1994, the first GUI case to ever go to court was when Apple sued Microsoft and HP for creating their own GUIs using Apple’s components. The court chose the Altai Test notwithstanding Apple’s arguments for protection under the concept and feel. The CJEU held that a GUI’s visual components are not protected by copyright. Soon after GUI developers sought protection elsewhere, including the design regime.

Coming back to the domestic scenario, there is an apparent lack of discussion around finding an IP regime suitable for safeguarding of GUI in the Indian Courts and statutes.

In India, the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology states that, ‘computer programmes are protected as a literary work by the Indian Copyright Act and hence, the look and feel of Graphical User Interface (GUI) can be protected under the Copyrights.’

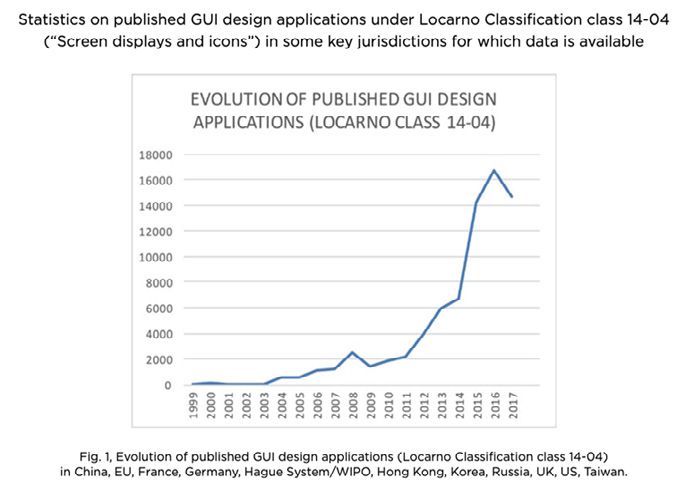

On the contrary, ‘GUI, computer screen layout, and computer icon protection’ are specifically mentioned under Class 14-04 of the International Classification for Industrial Designs (known as “the Locarno Classification”) published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”). This is the globally accepted class under which GUI designs are registered, as it specifically caters to ‘Screen Displays’.

In fact, in India, the Design Rules 2001 were amended to adopt the latest Locarno Classification in 2008, and as a result, Class 14-04 for “Screen Displays and Icons,” was incorporated.

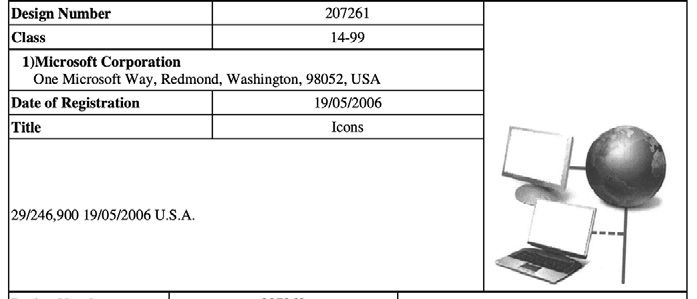

Subsequently, taking the benefit of Class 14, Microsoft got its GUI icons registered under Class 14-99, i.e. “Miscellaneous,” category.

The Design Act, 2000 (“Act”) under Section 2(a) lays down that article refers to any article of manufacture and any substance, artificial, or partly artificial and partly natural; and includes any part of an article capable of being made and sold separately. Furthermore, under Section(d) of the Act, design has been defined as only the features of shape, configuration, pattern, ornament or composition of lines or colours applied to any article whether in two dimensional or three dimensional or in both forms, by any industrial process or means, whether manual, mechanical or chemical, separate or combined, which in the finished article appeal to and are judged solely by the eye.

Focusing on these definitional limitations, one can very well conclude that GUI is an element of a display device, such as a computer screen, which is a manufactured good and is sold separately. As a result, a GUI satisfies the Design Act’s Section 2(a) requirement.

Moreover, GUI is a product comprising of configuration, pattern, ornament or composition of lines or colours; and is applied to the computer screen using a mechanical industrial process and qualifies as a “finished article” because it is a part of the product the customer purchases and is visible as soon as the device is turned on, thus fulfilling the requirements of Section 2(d) of the Designs Act.

Another essential factor that must be highlighted is that the design statute nowhere states that the design must be ‘constantly’ visible to the eye. In fact, the Manual of Design Practices & Procedure explicitly states that “Design features which are internal but visible only during use, may be the subject matter of registration”. For instance, features of an openable/sliding cell phone which are not perpetually visible, can be registered along with the closed views of the article for design protection.

In Ferrero and CspA’s application (1978 RPC 473, HL) the inner layer of a chocolate, which formed an essential part of the design, was upheld as a registrable design and the court observed- “I think it is fairly plain that the underlying reason was that the design feature was present all the time, even though it only becomes apparent when the article, that is to say the egg, was being used for its purpose, when it had been broken so that it could be eaten.”

Consequently, once the display screen is switched on, the GUI design is visible. Hence, squarely fitting under a design protection.

It is imperative to note that under Section 2(a), it is nowhere stated that the article has to be in physical state only, and cannot be virtual.

In fact, the recent Design (Amendment) Rules 2019 welcomes the latest version of the Locarno Classification comprising of Class 32 as a step towards harmonizing the design law in India with WIPO standards. The new Class 32 envisions protection for Graphic symbols and logos, surface patterns, ornamentation, evidencing that virtual designs also come under the ambit of articles under the Act.

This brings us to the looming question- if GUI can be protected under both copyright and design law, then where is the ambiguity?

As per the Indian laws one cannot be protected both under the Copyright Act as well as the Design Act at the same time. The Copyright Act, 1957 tackles the issue of dual protection under Section 15 (“Section 15”). This Section explicitly states that copyright shall cease to exist in a work eligible for design protection if the article to which the design is applied is reproduced more than fifty times by an industrial process, making the protection under copyright and design laws mutually exclusive of one another.

Scenario 1: Reproduction of the article

The term “industrial process” under Section 15(2) of the Act, is accompanied with the phrase “the production of the article for more than fifty times”.

The article to which a GUI design is applied would be the display screen. Hence, going by the literal definition, reproduction of the article would mean reproduction of the display screen.

Therefore if the number of manufactured display screens, showcasing the GUI goes beyond the number fifty, it would cease to have copyright cushion as well.

In this situation, reproduction of a GUI of a website could be ascertained from the number of visitors on the website. Supposedly the relevant website having the GUI is accessed with fifty different internet protocol addresses, it could be presumed that the GUI was reproduced fifty times.

The reproduction in the case of mobile application GUIs, could perhaps be linked to “installations”. Therefore, if the number of installations of the GUI/mobile application goes beyond the number fifty, it would cease to have copyright protection as well.

Hence, even though a GUI could initially be protected under the copyright, its commercial reproduction more than fifty times would render the copyright in the GUI ineffective. Further, the design registration of the GUI cannot be procured subsequently, because it will already in the public domain, eventually stripping the GUI developer from protection under both the laws.

Needless to say, this is only an analytical point of view and the actual uncertainty as to the practical applicability of GUI protection and the interplay with Section 15 can only be understood once the judicial perspective is stirred into play.

Undoubtedly, GUIs are extremely advantageous in distinguishing and developing ones brand, especially with the rising convergence of essential features and functionalities in the digital world. Making deliberate expenditures to secure this crucial intellectual property for your app/website makes sense whether you are a start-up or an established business.

While a GUI as of now finds place of protection under both Copyright and Design Act in India, but what happens when the infringer plays the Section 15 card at the time of dispute?

In light of the dual IP protection conundrum, it can be understood that Section 15 of the Copyright Act could certainly apply in the context of GUIs. Which basically means that reproduction of GUI more than fifty times would create a deadlock in the commercially competitive climate.

Hence, it is safe to say that the holistic and long term protection of a GUIs aesthetic appeal should come under the ambit of Design Act. Having said that, an amendment in the original Designs Act would be desirable to clear the clutter once and for all. This could perhaps be in the form of explicitly including virtual articles as a part of Section 2(a) and Section 2(d) of the Act.

Lastly, it cannot be ruled out that the new Class 32 for ‘graphic symbols and logos’ in India will support a reinterpretation of Sections 2(a) and 2(d). Hence, the very introduction of Class 32 is a ray of hope towards technological advancement, and shall shed better clarity towards the suitable IP regime for the GUIs.

While the above analysis reflects that IP protection for GUI remains fluid and uncertain in India, the comparison has to be made by the designers as to which rights would be commercially beneficial to them. It seems rather prudent to get a GUI protected under the design law before it goes into the public domain, to ensure that “all rights” are indeed reserved for the market players and an arbitrary number of reproduction doesn’t take away the imperative rights.

Mohit Goel is a Partner at Sim And San. Mohit’s expertise extends to dispute resolution in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and Arbitration and Conciliation. Mohit has played and continues to play a key role in some of India’s biggest Intellectual Property disputes. Mohit is also an active member of the International Trademark Association (INTA).

Mehr Bajaj is an Associate with Sim and San. She comes with a flavoured experience in the field of IPR. She renders opinions on Trade Mark, Advertising, Design and Copyright Law.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved