or

Mergers and acquisitions are strategic decisions taken for maximisation of a company’s growth by enhancing its production and marketing operations. They are being used in different industries viz. Information technology, telecommunications, and business process outsourcing apart from traditional businesses in order to gain strength, expand the customer base, cut competition or enter into a new market or product segment.

Mergers and acquisitions are regulated under various laws in India. The objective of the laws is to make these deals transparent and protect the interest of all shareholders. Firstly they are regulated through the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956.

The Act lays down the legal procedures for mergers or acquisitions. The other Act which regulates mergers and acquisitions include The Competition Act, 2002, as amended by The Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007.

The Act regulates the various forms of business combinations through the Competition Commission of India (CCI). Under the Act, no person or enterprise shall enter into a combination, in the form of an acquisition, merger or amalgamation, which causes or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition in the relevant market and such a combination shall be void. Enterprises intending to enter into a combination may give notice to the Commission, but this notification is voluntary. However, all combinations do not call for scrutiny unless the resulting combination exceeds the threshold limits in terms of assets or turnover as specified by the Competition Commission of India. The Commission while regulating a ‘combination’ shall consider the following factors:-

Thus, the Competition Act does not seek to eliminate combinations and only aims to eliminate their harmful effects.

Industry’s worries included the Act shifting to a mandatory notification regime from the earlier voluntary system. The mandatory regime requires companies that enter into mergers and acquisitions and meeting the asset/turnover thresholds specified in the Act seek prior approval from the CCI.

The earlier 90-day timeframe for clearance of mergers and acquisitions by the CCI had been enhanced to 210 days, which was considered too long a time by industry. Another issue was whether sectoral regulators will only give inputs to the CCI on mergers and acquisitions in their sector or if they would have the final say.

In the US, once a company makes a notification, the authorities have 30 days to review it. William Blumenthal, Partner at the global law firm Clifford Chance and chairing its US competition law practice, said the official agency can act fast if a request for swift action is made.

“At the end of 30 days, if the agency does nothing, you are cleared as a matter of right,” said Mr Blumenthal, former General Counsel of the US Federal Trade Commission.

In the US, the form on merger details is just 15 pages long. The questions are simple and include the names of the companies, contact addresses, description of the transaction, copies of securities filings, copies of official analyses of the merger, revenues details, list of subsidiaries and products that overlap due to the merger, Mr Blumenthal pointed out.

Mergers, where there is no overlap between products or if the two companies are in fragmented industries, are cleared swiftly, he said.

In South Africa, too, clearance is swift. James Hodge, Managing Partner of the Competition and Regulatory Economics practice at Genesis Analytics, said the South African Competition Commission has 40 days to clear a merger.

Cases are put on the fast-track if there is no overlap between the operations of the merging companies or if there is no competition issue. If the merged entity has a valuation that crosses the threshold, it is given a closer look, but this is also done in the 40-day period, he said.

“Only the complex or difficult cases take up to 45 or 50 days. But even the difficult ones should be done within 85 days, which is much lesser than the 210 days in India,” Mr Hodge said.

Generally only 2-3 per cent of mergers have competition issues that require government intervention, not to block, but to restructure them, Mr Blumenthal says, adding that “around 80 per cent of transactions are not problematic”. Delaying mergers may create problems in the realisation of the merged entity’s efficiencies and would increase employees’ concerns about their jobs. Countries should have an anti-monopoly legislation that

helps authorities quickly deal with mergers that are not problematic and focus on the difficult ones, says Mr Blumenthal.

As far as the justification for making notification of combinations (mergers and acquisitions) in India mandatory, the CCI had thought that with development of infrastructure in different sectors like electricity, telecom, roadways, airways, etc., a lot of combinations are destined to take place between Indian and foreign companies. In that perspective, the CCI can regulate combinations that cross the threshold limit created by the Competition Act, 2002, as amended by the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007; only if the notification is made mandatory. If it was voluntary, many companies could have escaped the review of the CCI in spite of crossing the threshold limit.

The Competition Act, 2002, as amended by the Competition (Amendment) Act, 2007, had been enacted after examining the competition laws of most of the other countries of the world, like US, UK, Canada, etc. Most of the countries had mandatory notification and India is no exception to it.

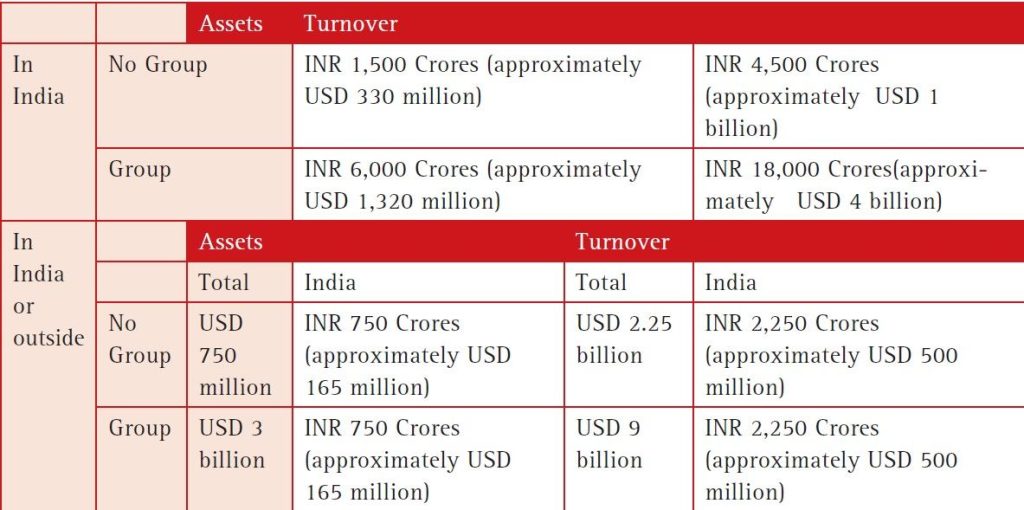

The CCI had brought in Amendment Regulations in 2011 and 2013 to amend the thresholds and process relating to combination review under the Competition Act. In 2011, the following asset and turnover threshold had been created.

According to that regulation, the value of assets includes the brand value, goodwill, value of intellectual property, but not the depreciation.

It can be said that Indian competition regime is its infancy. After the enactment of the Act, hardly five years had not elapsed. In that scenario, any provision under the new law can be analysed on the basis of experiences from foreign countries. There are not many cases in India that can be studied to back up the efficacy of mandatory regime. However, it can be predicted that mandatory regime can bring many controversial combinations within the scanner of CCI and the combinations can be ratified after minor changes that are to be made according to the directives of CCI.

Souvik is Assistant Professor, National Law University, Jodhpur

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved