or

Each one of us has more than once read a fake news item believing it to be true. Fabrication, distortion and manipulation of facts to influence the public has been in existence since time immemorial. While sometimes it is satirical and amusing, many a times it is not so easily discernible as fake and leads to stress, panic, spreading of false information, stereotyping, propaganda, communal discord and other kinds of mischief which harms the social, political, cultural and psychological fabric of the society. With the growth in dependency of people on digital media for their daily news updates, the menace of fake news has become especially problematic for India in the past few years. The term Whatsapp University is very commonly used for fake news being spread through the popular messaging app. The algorithms of social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Wikipedia, etc. are manipulated to target the audience on a large scale making them vehicles of false and fabricated information. The present article explores the laws related to control the spread of fake news in India and whether they are enough to curb the significant harm that is caused to the public.

Fake news is false, fabricated or manipulated content, which is presented as news or information to deliberately mislead and misinform the audience. The far-reaching consequences of fake news items manifested themselves in various international and national scandals. In 2016 United States elections, Russia was accused of hacking and meddling in the presidential campaign with cyber attacks through thousands of fake accounts on Facebook and Twitter. It was reported that this interference by Russia was confirmed by the US security agencies and Hillary Clinton lost the election due to the fake accounts programmed to spread false news about her and Donald Trump. Most famous examples of the fake news doing the rounds during the election include endorsement of Trump by the Pope and alleging Clinton’s involvement in an underground human trafficking/pedophile ring at a pizza parlor (Pizzagate). Because of the reach of digital media and the difficulty in prosecuting the sources of fake news, political parties and its supporters have found more efficient ways to influence the millions of voters by spreading false and misleading information through social media handles, bots, etc.

Fake news is not just related to politics but is also rampant in areas such as medicine, stock markets, film industry, etc. In the case of the alleged death by suicide of Indian actor Sushant Singh Rajput, thousands of fake accounts were found on various social media platforms which became echo chambers of misinformation, fabricated stories and manipulated news articles regarding the actor and other actors/entities involved in the investigation including the Mumbai Police and the Central Bureau of Investigation. In 2013, fake video spurred communal passions and caused riots in Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh.

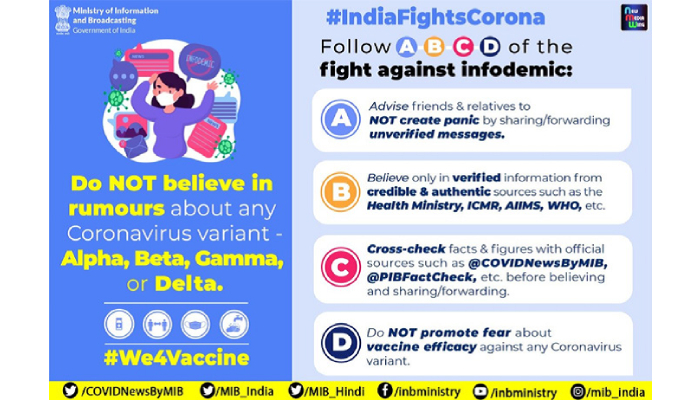

During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of false information regarding the virus has caused what the World Health Organization is calling, an ‘infodemic’ leading to scarcity of verified and reliable information when required. Due to the negative impact of such hoaxes and myths surrounding the novel coronavirus, about 400 Indian scientists have joined together to form Indian Scientists’ Response to COVID-19 which is committed to debunking false information about the virus such as – was Covid-19 made in a lab? Can air purifiers, cow dung or cow urine protect us from the virus? Do Indians have a better immune system against coronavirus? Certain non-profit websites such as Alt News, Buzzfeed, Boomlive, the Quint and some media houses such as India TV have also taken up fact checking the authenticity of sinister fake news items constantly doing rounds. In November 2019, the Government of India also gave the responsibility of fact checking and updating the public to Press Information Bureau (PIB), an agency under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Through its various social media pages and website (https://pib.gov.in/ factcheck.aspx), PIB spreads general awareness on fake news and verifies any news related to the government which is questionable.

The predominant reason for spreading of fake news in India is digital illiteracy. In fact, in May 2021 the Indian government was constrained to issue an advisory to various social media platforms to initiate awareness campaigns.

All around the world, the disinformation being spread through the online platforms has urged the governments to formulate specific provisions to curb and control fake news. In October 2019, Singapore implemented the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), to prevent the electronic communication of falsehoods (i.e. false statements of fact or misleading information) and put into place certain safeguards against the misuse of online platforms for the communication of such falsehoods. The POFMA in fact, gives sweeping powers to its ministers to decide what constitutes a breach which is inciting much ire in the international media. In April, 2020 Singapore authorities directed Facebook to disable local access to a page that purportedly contained false statements about its response to the coronavirus outbreak which was complied with within a span of twenty-four hours. It can be argued that Facebook was not given much choice as under the POFMA regulation it would have to pay hefty fines of about $14,400 a day.

While independent entities do their bit, India lacks a comprehensive legislation which would enable it to combat the menace of fake news. Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India provides for freedom of speech and expression because of which there is a constant legal struggle between regulation and complete restriction. In 2018, the Indian government in an attempt to deal with fake news brought out an amendment to the Guidelines for Accreditation of Journalists which provided for a stricter rule for cancellation of the accreditation of the journalists even prior to the fifteen days Inquiry procedure provided for. However, it led to massive protests by the media houses and the amendment was immediately withdrawn, within fifteen hours.

Regulatory bodies including Press Council of India, News Broadcasters Association, Indian Broadcast Foundation and Broadcasting Content Complaints Council have regulations in place to monitor the conduct of journalists, editors, newspapers, electronic media, channels, etc. for objectionable and fake content. However, these bodies have no control over fake news being disseminated online through all digital media and social media platforms.

The Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) contains provisions which criminalize fake news such as sedition (Section 124A); promoting enmity between different groups on ground of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc., and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony (Section 153A); sale, etc. of obscene books (Section 292); deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs (Section 295A); defamation (Section 499); criminal intimidation (Section 503); intentional insult with intent to provoke breach of the peace (Section 504); and statements conducing to public mischief (Section 505).

Out of all the above provisions Section 505 of the IPC casts a wider net and can be used to deal with sources of fake news. It provides that criminalizes making, publishing or circulating any statement, rumour or report which can result in ‘fear or alarm to the public, or to any section of the public whereby any person may be induced to commit an offence against the State or against the public tranquility’. However, just as wide the provision is, it also carries with it an equally lenient exception which exempts a person making, publishing or circulating any such statement/rumour/report if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is true and has made/published/circulated it in good faith and without any such intent. The exception therefore, dilutes the power and substance of the provision and practically renders it toothless.

In relation to the Covid-19 pandemic specifically, Section 54 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DMA) has been brought into operation which deals with ‘false alarm or warning as to disaster or its severity or magnitude, leading to panic’ which is punishable with upto one year imprisonment or fine. In April 2020, this provision was put into consideration before the Supreme Court of India by the Ministry of Home Affairs in a matter related to fake news items being run the news channels that the lockdown would last for many more months led to panic amongst the public, especially the migrant workers leading to panic and mass exodus. While hearing the matter the apex court directed the government to issue bulletins on the novel coronavirus every day and asked media to report the contents of the bulletin. Furthermore, it urged the media houses to maintain a strong sense of responsibility and to ensure that unverified news capable of causing panic is not disseminated.

For controlling fake news, the provisions of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) assume more importance than before. The IT Act was introduced to regulate the e-commerce infrastructure however, now it also encompasses within its ambit a framework to increase the accountability of publishers of online curated content and of news on digital media as well as providing the consumers of such published content with a redressal mechanism for their grievances. Earlier this year, the Indian government notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (IT Rules) introduced new mandates in Chapter V, Rule 18 whereby a publisher of news and current affairs content and a publisher of online curated content operating in India, shall inform the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting about the details of its entity by furnishing information and documents for the purpose of enabling communication and coordination. The IT Rules have also established a mechanism for redressal and timely resolution of the grievances raised by the users of social media platforms with the help of a Grievance Redressal Officer. The expanse of the new rules can be seen from the definition of a ‘Publisher’ which encompasses two types of publishers:

Both the definitions are very broadly worded and are inclusive in nature. Under the umbrella of ‘publishers’ in the IT Rules, almost every individual or organization is now covered which uploads and publishes content capable of being classified as news and current affairs (including analysis of any socio-political, economic and cultural content). In fact, a perusal of the definition of news and current affairs in Rule 2 (m) of the IT Rules would show that any kind of digital media which disseminates information online, the context, substance/purpose/import/meaning of which is in the nature of news and current affairs content is a publisher.

In addition to news and current affairs content publishers, Rule 2(s) also brings within its ambit other miscellaneous and independent individuals and entities which make available to the users, through subscription or otherwise, any kind of curated audio-visual content online. This expressly includes films, programmes, documentaries, videos, television programmes, serials, podcasts and other such content. Consequently, publishers under the IT Rules would include all and any OTT Platforms, independent commentators including Radio Jockeys, artists, comedians, etc.

While section 79 of the IT Act grants certain platforms protection from criminal action for third-party content posted on the websites by categorizing them as ‘intermediaries’ however, with the introduction of the new Rules, social media entities such as Twitter, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, Facebook and other miscellaneous publishers are required to regulate content; appoint nodal officers for compliance and grievance redressal; publish monthly compliance reports mentioning the details of complaints received and action taken on the complaints as well as details of contents removed; enabling tracing of messages and voluntary user verification; etc.. The IT Rules therefore, have been introduced to bring in a greater degree of social responsibility and transparency. The new Rules have also expanded the protection granted to women and children. It is now mandated that content depicting nudity or morphed pictures of women would be removed within twenty four hours from receipt of the complaint.

Furthermore, the IT Rules have introduced the concept of identification and disclosure of the ‘first originator of the information’ for prevention, detection, investigation, prosecution or punishment of an offence related to sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, or public order or of incitement to an offence relating to the above or in relation with rape, sexually explicit material or child sexual abuse material which is punishable with imprisonment for a term of not less than five years. This is extremely problematic for the social media giants, especially WhatsApp as it will have to break the end-to-end encryption privacy policy which ensures that no one in between can have access to the messages, photographs, video or audio files exchanged between persons, not even WhatsApp itself. While the objective of the Rules is purportedly self-regulation, the lack of procedural checks in between can lead to dilution of right to privacy as enshrined in the Constitution of India, grievous breach of personal data and initiation of arbitrary and illegal actions against citizens by the Government as well as the social media companies.

It is still to be seen whether these measures will prove effective enough to curtail fake news as the social media houses, artists and journalists have refused to accept the new IT Rules and have challenged them before the Madras and Delhi High Courts on the grounds of right to privacy. While the government is reformulating, the laws governing intermediary liability by increasing the social responsibility and accountability of the media platforms, it has not yet successfully formulated a compressive legislation governing the same. The digital media on the other hand is aggressively trying to retain its independence and privacy of its users. Free-speech advocates allege that the government is only trying to clamp down on its critics. Though born out of necessity, these laws can become powerful tools in the hands of an authoritarian regime and private corporations thereby defeating fundamental principals of freedom of speech and privacy laws. In this scenario it becomes even more paramount for the courts to remain vigilant to its abuse and most importantly for the users to be digitally literate and cultivate a habit of verifying the content online.

Sudeep Chatterjee is a Partner at Singh & Singh Law Firm LLP. He has handled various high - profile cases in the field of Copyright, Trademarks, Data Protection, Anti - Counterfeiting and UDRP. He was a part of the Parliamentary Standing Committee which was constituted to look into the Copyright Amendment Bill, 2010. He advises the DPIIT on Copyright related issues and is also on their panel. Since 2008, he has been a part of the INTA Committees - Trademarks Committee, the Non - traditional Marks Committee, and the Copyright Committee. Currently, he is a Member of INTA Enforcement Committee (2021 – 2023). He is also a member of the IP Committee of CII (Confederation of Indian Industry) and the India Working Group on Intellectual Property of ICC (International Chambers of Commerce).

Shifa Nagar is a Senior Associate in Singh & Singh Law Firm LLP, specializing in trademark and copyright litigation and advisory. She also has significant experience in the field of arbitration, and general civil and commercial litigation.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved