or

The enforceability of term sheets remains a contested issue in Indian contract law, especially in Venture Capital (“VC”), Private Equity (“PE”) and Mergers and Acquisitions (“M&A”) transactions. The recent decision of the Delhi High Court (“Court”) in Oravel Stays Pvt. Ltd. v. Zostel Hospitality Pvt. Ltd.1 (“Case”) offers significant guidance on this issue. The Case concerns a failed acquisition attempt by Oravel Stays Pvt. Ltd. (“OYO”) and the conflicting holdings of the Arbitral Tribunal and the Court regarding the binding nature of preliminary agreements. Critically, it highlights the limits of post- contractual conduct and the scope of arbitral authority.

Term sheets are foundational documents in M&A, VC, and PE transactions. Typically, serving as a preliminary outline of the proposed deal terms, they set out intent and guide negotiations. However, their enforceability hinges on their drafting and particularly, whether provisions are stated as binding or non-binding.

Historically, Indian courts have affirmed that a document is non-binding unless it shows intent to create legal relations and contains all material terms. The OYO-Zostel Term Sheet (“Term Sheet”) expressly stated it was nonbinding, except for limited clauses on confidentiality, approvals, expenses, exclusivity, and dispute resolution. A dispute arose when Zostel claimed that it had fulfilled its obligations under the Term Sheet, but OYO failed to proceed with the acquisition. When OYO argued that the Term Sheet was non-binding, Zostel invoked arbitration under the Term Sheet. When the parties failed to resolve their disputes and disagreed on the appointment of an arbitrator, Zostel approached the Supreme Court, resulting in the Supreme Court constituting the Arbitral Tribunal to resolve the dispute.

The Arbitral Tribunal held that the parties’ post-execution conduct, such as Zostel’s transfer of employees, data, and documents, demonstrated an intention to be bound, despite the Term Sheet stating that it was non-binding. The Arbitral Tribunal further reasoned that such substantial performance rendered the Term Sheet binding, concluding that OYO had breached its obligations under the Term Sheet.

This approach, however, stands contrary to settled precedents. In Bank of India v. K. Mohandas2, the Supreme Court held that the interpretation of a contract must primarily rest on the express language used and cannot be overridden by subsequent conduct. Similarly, in Azeem Infinite Dwelling v. Patel Engineering Ltd.3, the Karnataka High Court emphasized that term sheets are preliminary documents and not contracts, unless they expressly intend to be binding. The Arbitral Tribunal had deviated from established contractual principles by treating a document expressly intended to be non-binding, as binding under the guise of party conduct. As a result, OYO challenged the award directing specific performance (“Arbitral Award”) and prayed that it be set aside by the Court.

The Court set aside the Arbitral Award under Section 34(2)(b)(ii) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. It held that the Arbitral Tribunal exceeded its mandate as the Arbitral Award conflicted with the “fundamental policy of Indian law” by granting relief without a concluded agreement. Crucially, the Court focused on the following three critical aspects.

Firstly, it reaffirmed the primacy of contractual text. Since the Term Sheet bound only select clauses, the Arbitral Tribunal’s overarching reliance on conduct was rejected as legally untenable.

Secondly, the Court held that specific performance cannot be granted without a concluded contract. Citing Indian Oil Corp. v. Amritsar Gas Service,4 the Court held that specific performance cannot be granted where an agreement is either “determinable” or incomplete on material terms. Since the Term Sheet deferred final obligations to future definitive agreements, which were never executed, it was held that there was no concluded contract, eligible for specific enforcement.

Lastly, the Court found the Arbitral Tribunal’s findings to be contrary to the fundamental policy of Indian law. Citing Associate Builders v. DDA5 and Ssangyong Engineering v. NHAI6, the Court clarified that an award which rewrites the contract terms or grants relief contrary to statutory limitations will fall foul of public policy. The Arbitral Tribunal’s decision was viewed as an overreach into contractual freedom and commercial certainty.

Another key issue was whether the parties’ post-signing conduct could transform a non-binding term sheet into an enforceable contract. The Arbitral Tribunal relied heavily on Zostel’s partial performance, due diligence access and OYO’s engagement with transferred resources. However, Indian courts have consistently drawn a distinction between negotiation-related conduct and contractual consensus.

Critically, Section 8 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, permits acceptance by conduct only if the underlying document is intended to be binding. The Court held that where a contract expressly disclaims binding effect, subsequent conduct cannot establish consensus ad idem. Therefore, though the Arbitral Tribunal held that the Term Sheet was binding due to creation of obligations and extensive due diligence undertaken on the basis of such Term Sheet, the Court held that post-signing conduct could not establish contractual enforceability.

This Case has wide-reaching implications for participants in India’s start-up and investments ecosystem.

Firstly, it reiterates the importance of precision in drafting. If parties intend a term sheet or Memorandum of Understanding to be binding, that intention must be clearly stated. Conversely, if they intend to reserve enforceability for definitive documentation, the language must unambiguously reflect that.

Secondly, this Case underscores the need for caution during due diligence prior to execution of final agreements. Premature integration or data access without contractual safeguards may expose parties to unintended claims, even if courts ultimately reject them.

Thirdly, this Case reinforces the necessity of robust dispute resolution and governing law provisions, especially in cross-border deals. The fact that the arbitration clause under the Term Sheet was held to be enforceable, even as other clauses were non-binding, highlights how parties may inadvertently subject themselves to full-scale arbitration over incomplete agreements.

Additionally, the Case furthers the evolving jurisprudence on the scope of “fundamental policy of Indian law” under Section 34(2)(b)(ii) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, particularly in the context of international commercial arbitrations where judicial review is narrow7. While reaffirming this limited standard of intervention, the Court held that the Arbitral Award effectively violated fundamental legal norms by enforcing the explicitly non-binding Term Sheet and granting specific performance in the absence of a concluded contract. In doing so, the Court invoked the public policy framework laid down in Renusagar Power Co. v. General Electric Co.8 and reaffirmed in OPG Power v. Enexio Power9, which clarify that enforcement of arbitral awards is impermissible where the tribunal disregards contractual language or awards relief in contravention of settled precedents by superior courts. Notably, the Court emphasized that this was not a reappraisal of merits, but an instance where the award had crossed the permissible line into legal incoherence.

The Court’s decision reaffirms the primacy of clear contractual language and delineates the limits of arbitral discretion, particularly regarding term sheets. It clarifies that such preliminary documents are unenforceable unless they expressly indicate an intention to create binding obligations. Neither extensive negotiations nor partial performance can override explicit disclaimers of enforceability. Obligations in commercial arrangements must be grounded in mutual consensus recorded in writing, not inferred retrospectively from conduct or operational cooperation. The Case underscores that in private transactions, party autonomy and documented intent primarily govern enforceability. It is this express consensus, not post-facto conduct of the parties that determines contractual enforceability.

Akanksha Dua, Associate at Obhan & Associates, focuses on diverse areas of Corporate and Commercial laws. Her practice involves structuring transactions, drafting, reviewing and negotiating a wide range of contracts.

Aastha Srivastava is a Senior Associate with the Corporate Law team at Obhan & Associates. She routinely advises clients on general corporate matters and regulatory compliances. She has experience in end-to-end contract management including drafting, negotiation and legal advisory on commercial contracts. She assists clients and companies operating in the technology, media and entertainment, and consumer products space.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

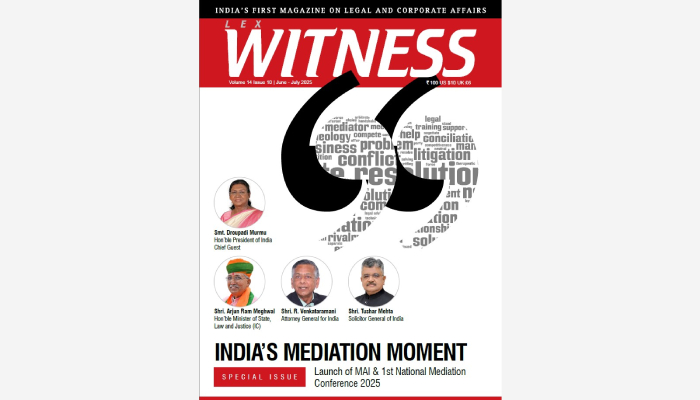

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved