or

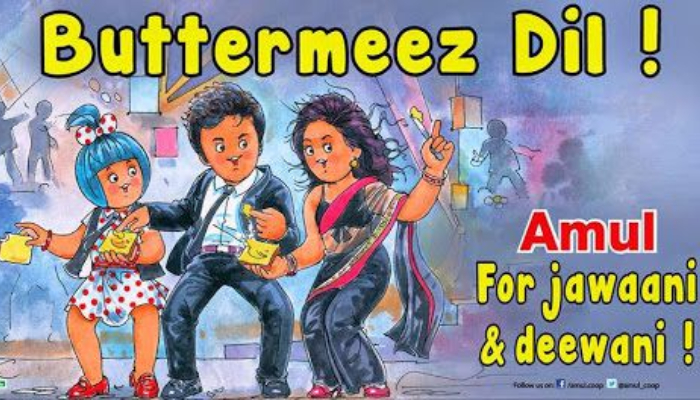

“Buttermeez dil”; “KabaliZing Butterfly”; “Aam Aadmi ho ya koi VIP, Amul butter lagaye toh har ek cheez tasty”; “In international news, aliens have confirmed they won’t visit Earth until we get our act together. So, no pressure.” Ring a bell? Well, here is a hint, these satirical parodies have been the oldest trend in India, gaining fame over the years. The history of such parodies in India can be traced back to the formation of political parties, their campaign commitments, and their swift dive into both Bollywood and the broader Indian film industry.

However, the major question revolves around the constitutional permissibility of these parodies. Even if they are deemed constitutionally permissible, the question arises as to the significance of intellectual property in these instances while sustaining the rights to free speech and expression.

Parody is a combination of comedy, satire, social criticism, and an old art form with the capacity to shock or offend its audience. While copyright and trademark protection aim to promote one or two major interpretations of a work, parody aims to achieve the reverse by promoting a diverse view. In India, the intersection of parody and trademark law often leads to confusion and legal debates. Parody, as a form of expression, involves imitating or mimicking an original work, often for comedic or satirical purposes. However, when parody involves the unauthorized use of trademarks, it can potentially conflict with trademark laws. How legal avenues balance conflicting interests in the context of trade mark infringement while upholding the rights to free speech and competitiveness, is a question to ponder over.

Commercial speech is defined as any expression that promotes a commercial transaction or is related to the speaker’s and audience’s economic interests. In the United States, important cases such as Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980)1 influenced the concept and protection of commercial speech. In this case, the Supreme Court developed a four-part test to examine whether commercial speech limitations were constitutional. Commercial speech is protected by the First Amendment, but the government has more authority to regulate it than non-commercial speech, as long as the laws serve a genuine government interest and are not overly broad. Non-commercial speech, on the other hand, refers to a wide spectrum of utterances that do not entail commercial transactions or economic concerns. Landmark rulings like Texas v. Johnson (1989)2 , which upheld the burning of the American flag as a form of expressive action, demonstrate the Supreme Court’s dedication to protecting non-commercial expression under the First Amendment. Non-commercial speech is often protected more than commercial speech.

When it comes to trademark infringement and free speech, it is critical to distinguish between commercial and non-commercial communication. Parody, which falls under the category of non-commercial communication, is frequently protected, even if it involves the use of a trademark. This protection is founded on the idea that parody is useful in social and political debate because it allows for criticism and discussion. In the landmark case Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994)3 , the Supreme Court held that a commercial parody, like the rap group 2 Live Crew’s parody of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” could be a protected form of fair use.

He Indian Context Unless the mark’s use is clearly misleading as to the source of the work’s content or is not artistically meaningful, free expression rights take precedence over trademark rights. The non-profit environmental organization Greenpeace was permitted by a French court to use a parody of the logo of the oil firm Esso on a website to criticise the company and its industrial activities, using the defendant’s fundamental right to freedom of expression. For identical reasons, the German Federal Court of Justice denied a trademark claim by a Marlboro cigarette distributor, as well as a request for an injunction to prevent an anti-smoking organization from using the Marlboro marks in a spoof advertising.

In cases of trademark infringement, the use of parody is often recognized as a legal defense. It has become common to alter movie titles, business names, and other designations for creating memes and satirical remarks. However, the question arises: does such modification amount to trademark infringement? This issue was addressed in the TATA case, where the primary focus of the court was on a potential violation of the Trademark Act.

“This defence was first discussed in the 2011 case of Tata Sons Limited v Greenpeace International (178 (2011) DLT 705), in which the primary issue before the court regarded a violation under the Trademark Act. Greenpeace – an organization which works for the protection of the environment – openly objected to Tata’s construction of a port by negatively depicting this in the online game Tata Vs Turtles, where turtles were portrayed escaping the Tata logo. Tata filed a petition for defamation and trademark infringement, and sought damages. Greenpeace countered this with the parody defence. The court found that Greenpeace was not liable on the following grounds:

Since the trademark was used in the context of the game to raise awareness, it was not deemed defamatory4 .”

Michael Spence, can IP scholar, noted, “parody’ (understood in the broad sense of the word, which includes also nonhumorous expressions) ‘provides good examples of the conflict that can arise between intellectual property and free speech.”5

Now, think about this: Your trademark, into which you’ve poured substantial funds for advertising, marketing, and more, likely carries not only financial value but also a sense of professional pride and self-worth, is being used as a subject of public humor. There is grave injury to one’s dignity and reputation. Even if, ultimately, we may argue that freedom of speech should take precedence in such instances, it doesn’t negate the reality of those potential harms to one’s reputation.

It appears more faithful to the actual conflict of interests and values in practical situations to use a language that acknowledges the reality of harm on both sides. Rather than disregarding one of the conflicting harms as legally insignificant, a more prudent approach involves recognizing both sides’ harm and subjecting them to a reasonable process of weighing and balancing.

The answer to this is a point well observed in a brilliant concurring opinion by Justice Sachs that ‘what is in issue is not the limitation of a right, but the balancing of competing rights’6 .

How can trademark law be balanced with other important constitutional interests, especially freedom of speech? In particular, it is essential to determine rights undermines the core essence of the constitutional right in question.

‘The Indian constitution and other national constitutions expressly recognise the right to freedom of expression. Freedom of speech and expression is the bulwark of democratic government. This freedom is regarded as the first condition of liberty. It occupies a prominent place in the hierarchy of liberties in preference to all other freedoms. Article 19(1)(a) guarantees to all citizens the right to freedom of speech and expression which includes right to express one’s views and opinions on any issue through any medium, e.g. by speech, writing, printing picture, film, music, movie etc.’7 . Furthermore, considering TRIPS’ stance on freedom of speech, it allows nations to uphold the right to freedom of expression within their national trademark laws. This is achieved by excluding certain specific terms or other ‘signs’ from the protected subject matter, narrowing the extent of rights granted by a trademark, introducing restricted exceptions to trademark rights, and customizing remedies in trademark disputes to safeguard speech interests.

Finding a balance between the protection of trademark owners’ brands from potential harm and the freedom of speech, including parody, is a difficult task. In trademark cases, courts frequently consider the total effect on customers’ perceptions as well as the likelihood of confusion when judging whether parodies are allowed.

For example, Amul, the Indian dairy cooperative, is renowned for its topical and witty cartoon advertisements commenting on current events. These often involve a play on words and parody of famous trademarks or personalities. For instance, during the release of a popular movie, Amul might create a cartoon that humorously incorporates elements of the film. While Amul’s approach is generally well-received, it does highlight the fine line between parody and potential trademark concerns; In online Merchandise and Parody, independent artists and online platforms sometimes create parody merchandise that includes well-known brand logos or symbols. For instance, satirical versions of popular logos may be used to create T-shirts or accessories with a humorous or critical message. If these items gain attention and there’s a risk of consumer confusion, trademark owners might take legal action.

A nuanced and context-specific approach is ultimately needed in order to achieve an optimal balance between ensuring the fundamental right to freedom of speech and keeping the brands of trademark owners from potential harm. The details involved reflect how this legal environment is fluid and calls for constant scrutiny of the fine balance between these conflicting rights.

The reasoning offered here should bring mark owners to the realisation that, properly defined, trademark law cannot and should not in most situations compensate harm caused by expressive uses, regardless of their unwholesomeness. The key consideration for courts and trademark owners is whether a certain usage is truly expressive or creative, or if it is commercial and may be more liable under trademark law.

This distinction—rather than the contrast between a positive and negative portrayal—is what counts in the end when it comes to the application of dilution responsibility. Trademarks are no longer the sole property of their holders since they have developed into brief representations for ideals, concepts, and experiences in our popular culture.

Rather, trademarks become the acceptable subject of satire or the cinematic vision of a filmmaker when they are incorporated into a creative work. As Judge Kozinski observed: “When the public gives a trademark owner’s mark a meaning beyond its source-identifying function, the trademark owner does not have the right to control public discourse”. The correct distinction between trademark law and free expression forbids trademark owners from controlling the appearance or use of their trademarks in non-commercial contexts. Perhaps in the future, that sphere’s definition will shift, leading to a corresponding reconsideration of the trademark law’s bounds.

The firm acknowledges contribution from Sristi Chowdhary who contributed majorly to the article.

Mohit Goel is a Partner at Sim And San. Mohit’s expertise extends to dispute resolution in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and Arbitration and Conciliation. Mohit has played and continues to play a key role in some of India’s biggest Intellectual Property disputes. Mohit is also an active member of the International Trademark Association (INTA).

Paridhi Tyagi is an Associate Partner. Paridhi has a robust experience of over a decade now in the field of Intellectual Property laws and has represented numerous leading Indian companies and Multinationals, including Fortune 500 companies. She specializes in providing strategic advice on handling global trade mark portfolios, brand protection and enforcements, brand licensing and acquisition of intellectual property assets and conducting intellectual property-related due diligence.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved