or

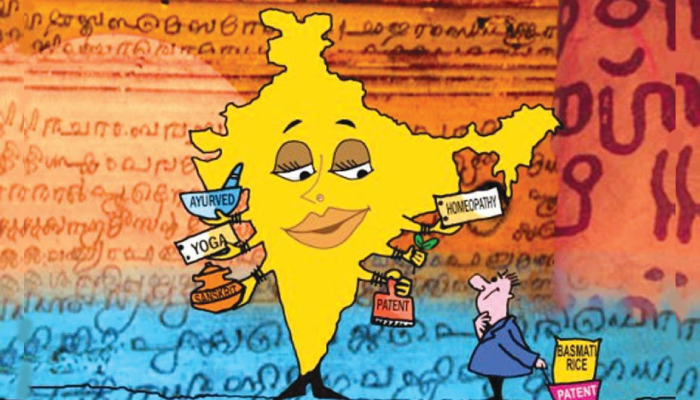

The leitmotif of this article is to discuss in brief the on-going attempts at evolving a sui generis model of protection for Traditional Knowledge (TK). In the process, the article raises certain fundamental questions regarding the nature of TK, its inclusive recasting in recent times and the volution of a balanced duty and rights-based jurisprudence to address issues Central and ancillary to traditional knowledge. This includes but is not limited to the involvement of indigenous groups in discussions and decision-making on TK and recognising that preserving the indigenous groups’ way of life is inextricably intertwined to preservation and protection of TK. The article finally concludes advocating an approach which allows for incentivising individual creativity within the bounds of a community-oriented framework to ensure survival of traditional forms of art.

For over two decades now, Traditional Knowledge has been discussed with a lot of enthusiasm, which is evident from the sheer quantum of literature produced on it. If one were to chart patterns in the literature that has been produced so far, the patterns would reveal a gradual but definite increase in the maturity with which the subject of TK has been approached. Beginning with literature expounding on the uses of TK, its nature and the difficulties associated with characterising it were subsequently paid attention to. In the process, it was realised that TK represents a virtually replenishable goldmine for private interests and thus, began a phase when discussions revolved around TK and its misappropriation by enterprising individuals.

Naturally, at some point, the foundations for a rights-based discourse had been laid, which triggered an extended period when the interaction had a perceptible degree of tumult. During this period, the schismatic pathology, which had come to plague every discussion on TK and the law, was further exacerbated when it was suggested that the very collective and incremental nature of TK presents an incongruity to conventional western perceptions of science and proprietary jurisprudence, specifically Intellectual Property (IP) jurisprudence.

The constant sparring between the two warring schools of thought, inevitably, had to reach an impasse. It was then decided that there were only two realistic courses of action open – the first, where attempts could be made to harmonise TK with IP, and the second where a distinct or sui generis form of IP could be evolved for TK. The primary issues, which figured throughout these phases and still figure the solutions proposed and the way forward, form the rest of this article.

Law being a definitional discourse, semantics play a significant role in determining the truth value of propositions made and conclusions reached. It is therefore important to understand how the term ‘Traditional Cultural Expressions’ (TCEs) has come to replay TK in formal and informal fora. Earlier, the term ‘Traditional Knowledge’ was, at times, crudely substituted with “folklore” and it was felt that the latter was derogatory, since it appeared to treat indigenous groups as (oxymoronically) inferior civilisations and their traditions as superstitions or at best pseudoscience, which were yet to measure up to “modern” mores and science. It was thus decided that the language and tone of the dialogue itself had to change, if both parties were to be considered and treated on par.

Accordingly, in the sixth report of the Inter-governmental Committee Report on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore, the term TCE was introduced to reflect the value systems of indigenous groups and to reinforce their heritage and worldview. According to the said report, TCEs act as sources of inspiration for practitioners of traditional arts, and hence, they need to be protected. The question, which must be asked here, is what constitutes ‘protection’? Is ‘protection’ the same as ‘preservation’?

‘Protection’ stands distinguished from ‘Preservation’ since the former refers to either authorising or excluding one from exercising any rights in respect of such expressions, whereas the latter refers to mobilisation of resources to ensure the continued survival and perpetuation of the expressions.

Further, protection means protection against injury and more importantly, against derogatory and offensive use. The injury to a community’s cultural expressions could be in multifarious ways such as intrusion into their privacy, passing off their identity, stereotyping their customs and accessing their literature without their consent. The right against such injuries falls within the penumbras of a much wider concept of ‘Cultural Rights’. Though such rights are deemed to inhere in indigenous groups, the necessity for their assertion arises when indigenous groups interact with the rest of the world, outside their community. This interaction again raises a few pertinent questions with regard to cultural rights in TCEs.

First, if indigenous groups decide to allow themselves and their TCEs to be subject to scrutiny by rest of the world, does it prevent them from seeking isolation again? In other words, is the change in their status irreversible? Such a conclusion would be draconian and would defeat the very objective for which protection of groups is sought, since groups need greater during interaction. The reason being that indigenous groups could be taken for a ride on account of their ignorance of the law, in which case the party which accrues benefits would go scot-free, taking undue advantage of the groups.

Accordingly, not only should indigenous groups have the liberty to choose if they seek interaction, but also the limits and mode of interaction would have to be left to their discretion with generous help from the law. This means that besides the right to object to commercial use by others and the right to commoditisation which vests with the groups, the groups may assert their right to be “left alone”. Some argue, that this would mean encouraging preferential treatment of such groups to the detriment of others. It has to be understood, that although the law has a distinct Kantian tilt (“Greatest Good of Greatest Number”), it does not and cannot permit emasculation of the rights of one group at the altar of “the larger good”.

Second, what is the scope and extent of cultural rights of the groups in TCEs, which the law deems fit for recognition? In other words, how small is small and how big is big an injury for redressal in and by a court of law? Since subjectivity is inherent in this question, the answer is best left to the factual matrix of each case. Prescribing a de minimis line may not do justice to the nature of the subject-matter.

The third issue is the most crucial of all. Can the State or a conglomerate of States (in the form of a treaty) decide upon the criteria for defining the rights of groups without taking into account the customs of groups? When custom has the force of law in accepted commercial practices, can customary law form the basis for indigenous jurisprudence? Or can we coerce indigenous groups into accepting our definitions of their personality? Also, violation of customary law could lead to loss of privacy of groups, which no amount of monetary compensation or damages can make good. This is all the more relevant since if damages were a way out of such cases, every entity with heaps of greenbacks would violate customary laws with impunity no thanks to its financial clout. This explains calls from certain quarters for imposing a criminal deterrent.

Finally, it is to be noted that the law, which deals with reputation and cultural rights in cultural expressions, must not have a fixed boundary for, to delimit it would be self-defeating. Therefore, flexibility is a cardinal prerequisite to protect traditional expressions since such expressions are distinctive on account of their centrality to the lives of the groups.

Shamnad Basheer Ministry of HRD Professor in IP Law, National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata

Firstly, it is important to appreciate that all kinds of Traditional Knowledge (TK) cannot be lumped together under one common regulatory or legislative umbrella. One must make a distinction between “functional” TK and “expressive” TK. Functional TK would include things like traditional medicinal knowledge, traditional methods of farming etc. Expressive TK would include things like folklore, traditional songs, dance forms etc and all that is now included within the concept of Traditional Cultural Expression (TCE).

Since I am particularly interested in traditional medicinal knowledge, I will restrict my comments to this area. But first, let me take the issue of terminology. The term “traditional” knowledge is a bit confusing, since it literally connotes anything “old”. And could therefore include even western scientific achievements of the last century! What might be more preferable is the term “alternative knowledge”, since most of the TK talk doing the rounds today embodies some kind of an alternative knowledge epistemology.

India is particularly rich in various forms of Alternative Medicinal Knowledge (AMK); little wonder then that the government is scrambling to legislate on the area. However, this is a very tricky terrain and one must proceed cautiously. There appears to be three broad imperatives:

Trade secrecy protection appears an apt mode of protection here and India must legislate immediately to provide such community based trade secrecy protection. Once such protection kicks in, indigenous tribes can transfer such knowledge safely under a contract.

However, the State must ensure that such contracts are respected only when the terms are fair and there is “informed” consent from the tribes.

To conclude, India must take proactive steps to leverage its ancient wisdom. It is high time that we take a leap from the Green revolution to the Neem Revolution!

Over the past decade, bio-technological, pharmaceutical and human health care industries have increased their interest in natural product as a source of new bio-chemical compounds for drug, chemical and agro-products development. The decade has also witnessed a resurgence of interest in traditional knowledge and medicine. This interest has been stimulated by the importance of traditional knowledge as a lead in new product development. It is estimated that of the 119 drugs developed from higher plants that are in the world market today, around 74 per cent were discovered from a pool of traditional herbal medicine. In 1990, Posey estimated that the annual world market for medicines derived from medicinal plants discovered from indigenous people amounted to US$ 43 billion. A report prepared by the Rural Advancement Fund International (RAFI) estimated that at the beginning of the 1990s, worldwide sales of pharmaceuticals amounted to more than US $ 130,000 million annually.

India does not have any specific legislation for protecting traditional knowledge. But the Patents Act, Plant Variety Protection and Farmers Rights Act, Biological Diversity Act, 2002 and Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 2002 and Geographical Indication of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 have provisions that can be utilised for protecting traditional knowledge. The concept of benefit-sharing, which is an integral part of protecting traditional knowledge, has been analysed in detail with specific reference to the Biological Diversity Act and also the Plant Variety Protection and Farmers Rights Act. The case study of Jeevani drug gives an insight into the concept of benefit sharing. The importance of traditional knowledge is highlighted in the revocation of patent granted to derivatives of neem on the ground that they were part of the traditional knowledge of our country and that fungicide qualities of the neem tree and its use had been known in India for over 2,000 years. Also, case studies of Basmati and the protection granted to Pochampilly Saree and ranAmula Kannadi helps to have an in-depth understanding of the significance of geographical indication in the protection of traditional knowledge.

It is a sorry state of affairs that there are no uniform norms regarding the protection of different types of traditional knowledge owned by local communities. The reason for this divergence of laws is that the international community never had an occasion to look at the protection of traditional knowledge in its entirety. Measures to ensure that traditional knowledge is protected should be taken at the auspices of the WTO which should lay down general mandatory provisions to be complied by member countries. The pressing need of the hour is to enact a sui generis, or alternative law to protect traditional knowledge. The following measures can be followed to ensure the effective protection of traditional knowledge:

Sui generis protection is a customised form of protection, which not only recognises the inadequacies of existing forms of IP rights, but goes a step further to create another form of IP to effectively protect a particular species of property. In that broad sense, every form of IP is sui generis to the subject-matter it protects. Further, opting for a sui generis model of protection may not necessarily mean that harmonisation between the existing IP framework and TCEs is impossible; it only means that a sui generis form of protection is better placed to address the protection of TCEs holistically, as opposed to a force-fitted patchworked middle path model.

Refreshingly, the revised World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) Inter-governmental Committee draft provisions on sui generis protection have been widely acclaimed for being progressive. The all-embracing tone of the draft provisions is evidenced from the latitude provided to the definition of TCEs in Article 1, which is as follows:

verbal expressions, such as: stories, epics, legends, poetry, riddles and other narratives; words, signs, names, and symbols; musical expressions, such as songs and instrumental music; expressions by action, such as dances, plays, ceremonies, rituals and other performances, whether or not reduced to a material form; and, tangible expressions, such as productions of art, in particular, drawings, designs, paintings (including body-painting), carvings, sculptures, pottery, terracotta, mosaic, woodwork, metal ware, jewellery, baskets, needlework, textiles, glassware, carpets, costumes; handicrafts; musical instruments; and architectural forms;

which are:

The freedom given to municipal States to choose their own terminologies is consistent with the recognition of the contextual nature of TCEs. Further, not only do the draft provisions acknowledge and hence protect the product of traditional knowledge –TCEs, but also impute legal validity to the indigenous processes and customs. Accordingly, article 5 of the draft provisions provides for communication and transaction of such TCEs in accordance with customary laws. The article recognises customary laws in all contractual transactions to which indigenous groups are a party. As regards the term of protection, article 6 states that TCEs shall retain the status of TCEs as long as they conform to the definition in article 1.

The underlying idea behind these provisions is reflected in its assumption that since TCEs bear a strong imprint of the community and its traditions… “…even where an individual has developed a tradition-based creation within his or her customary context, it is regarded from a community perspective as the product of social and communal creative processes. Accordingly, the creation is, therefore, not “owned” by the individual but “controlled” by the community, according to indigenous and customary legal systems and practices.”

Although this assumption is well-intentioned, it may inadvertently contribute to the extinction of TCEs for lack of an incentive, which motivates individuals to invent and experiment with TCEs. The existing forms of protection to certain TCEs in the form of Geographical Indications (GIs) may be successful in ensuring that the identity of the community and its contribution to the TCE are duly recognised. However, if a mechanism for rewarding individual creativity and simultaneously preserving the integrity of TCEs is not devised, stagnation and subsequently extinction would be the utterly undesirable yet logical conclusions.

It cannot be denied that the debate on TK and TCEs has come a long way, which is evident from the quality and tone of the debate. It said that if TCEs are to retain their rightful place under the sun in a competitive market, encouraging innovation from within and outside indigenous groups is necessary. Therefore, the attempts of all stakeholders in the TK debate must be to synthesise a unique model, which ensures that TCEs do not remain mere relics of the past.

Saikrishna Rajagopal, is the Managing Partner of Saikrishna & Associates. He has worked extensively on a broad spectrum of Civil and Criminal Intellectual Property litigation in India for distinguished foreign and domestic clients. Saikrishna is also a renowned expert in the field of software anti-piracy initiatives.

J Sai Deepak, an Associate in the Litigation Team of the firm Saikrishna & Associates. Sai primarily handles patent litigation. Sai Deepak is an avid blogger on the reputed Indian IP law blog SpicyIP. His post on the Bajaj-TVS patent dispute was cited extensively and relied upon by a Division Bench of the Madras High Court.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved