or

Business strategies in an economy need to be designed and rejigged keeping in view the regulatory structure and the transforming legal framework. In India, the paradigmatic shift from the erstwhile MRTP Act to Competition Act in India was necessary to infuse and promote a culture of competition. The basic purpose of competition law is to promote competition through the control of restrictive and anticompetitive business practices. Competition Act chalks out a wide mandate for Competition Commission of India (CCI) as has also been affirmed by decision of the Supreme Court in CCI v. SAIL in 2010. The substantive provisions of the Act dealing with anticompetitive agreements and abuse of dominance came into effect in May 2009, there by completing five years of enforcement.

It is important to mention that India has a civil penalty regime and not a criminal penalty as in USA. There is no criminal liability from the violation of the substantive provisions of the Competition Act in India. However, non-compliance with the orders issued by the CCI could result in criminal liability by way of a fine up to INR 25 crores and/or a prison sentence up to a maximum of 3 years. Similarly, noncompliance with the orders issued by the COMPAT could result in criminal liability by way of a fine of up to INR 1 crore and/or a prison sentence up to a maximum of 3 years. In such cases, the punishment is to be imposed by the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, Delhi, pursuant to a complaint filed by the CCI or the COMPAT, as the case may be.

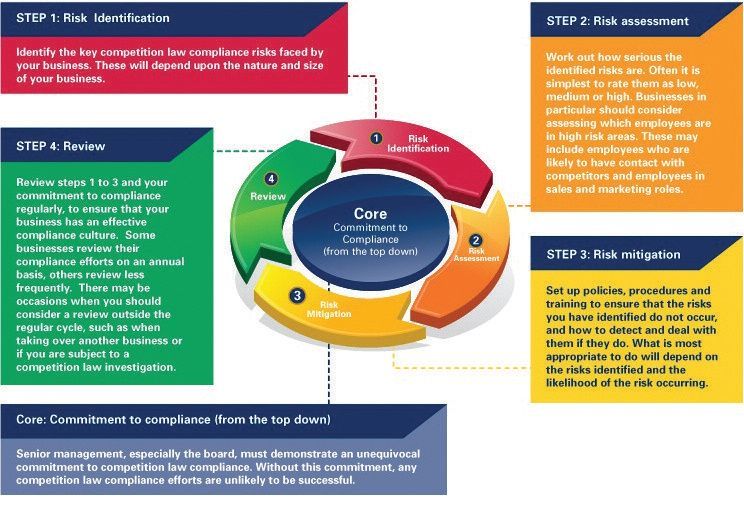

Action of competition authorities in form of competition advocacy, orders, guidelines, regulations and other measures are the signposts for the businesses to gear up for the competition law compliance. UKs competition authority describes compliance as a four step process including risk identification; risk assessment; risk mitigation and review. Commitment to competition compliance throughout the organisation should lie at the core of this four step process. Figure 1 is selfexplanatory and describes the steps involved in the cycle of competition law compliance.

CCI has come a long way since its first cartel decision of May, 2011 when associations of film producers got away with a token penalty. The article aims at highlighting five major trends in the approach of levying penalty by CCI in these five years of enforcement of provisions related to anticompetitive agreements and abuse of dominance violations.

Five specific trends in these five years of coming into force of stated provisions canbe discerned from the orders of the CCI. First, CCI has started levying high penalties. Though, it is debatable whether the amount of penalties imposed are proportionate to the anticompetitive conduct and effect of the enterprise fined, yet the amounts are enormous keeping in view generally penalties levied for non-compliance of laws in India have been meagre. This is also important because the erstwhile MRTP lacked such powers and was the major reason for ineffective MRTP regime in India.

Second, personal liability is also being read in to the Act. Section 48 of the Competition Act, 2002 provides that those directors and other officers who are in charge of the affairs of the company to be personally liable, where their actions result in the company falling foul of the rules, regulations or orders passed under the Act. In a recent order against Bengal Chemist and Druggist Association, CCI not only penalised the association for its anticompetitive conduct but additionally held its senior officials to be personally liable and fined them for endorsing such anticompetitive conduct of the association.

Third important development is that CCI has ratified the principle of competitive neutrality and has also fined Coal India Ltd., a public sector undertaking, for abusing its dominant position. The Act rightly enshrines the principle of competitive neutrality and the action of CCI endorsing this principle is a laudable step. Fourth, CCI has started levying fines on the firms for non-furnishing of the information being asked for. Recently, Google was fined Rs 1 crore by CCI for failure to comply with the directions given by the Director General (DG) seeking information and documents.

Lastly and more importantly, CCI has recently started giving reasons for quantifying penalties. If we analyse the orders of CCI, earlier CCI was not providing any reasons for levying fines on the infringers. It was only after the observations by Competition Appellate Tribunal (COMPAT) that CCI has started doing so. This is again a welcome step and will help in developing healthy jurisprudence in this field. In Coal India order, CCI held that twin objectives behind imposition of penalties are to impose penalties on infringing undertakings which reflect the seriousness of the infringement and to ensure that the threat of penalties will deter both the infringing undertakings and other undertakings that may beconsidering anti-competitive activities from engaging in them.

It is important to see that yet there are no penalty guidelines in India, as has been seen in mature jurisdictions like EU and USA. Mature jurisdictions have developed penalty guidelines to bring in transparency and predictability. This brief analysis of the five years of working of CCI and the trends of levying penalties clearly show that CCI is learning fast and is open to effectively use powers granted under the Act.

The prospect of damage to reputation, individual sanctions and heavy financial penalties are the key drivers for businesses for taking up competition law compliance. Generally, it has been seen in the mature jurisdictions that companies incorporate a competition law compliance programme. Such a compliance based competition culture needs to be incubated in India also. This is more important when the business mind-set in India still perceives benign some business practices which can fall foul of Competition Act. A good example is the role of trade associations being examined and found problematic in some cases by CCI. Competition law compliance is now gaining impetus in newer jurisdictions due to proactive enforcement strategy adopted by competition authorities. The changing trend discussed above, as is evident from the orders of CCI, clearly indicate that businesses need to adopt a proactive compliance based approach. Further, only setting up a competition law compliance programme would not help, unless the employees are given proper training related to this intricate and emerging branch of law. Competition law compliance can be a part of broader compliance agenda and needs to be incorporated in business’s overall corporate responsibility framework.

The mandate given to CCI under the Act and the trend in levying penalties in these five years of coming into force of provisions related to anticompetitive agreements and abuse of dominance clearly show that CCI will effectively use its teeth if enterprises indulge in anticompetitive practices. These developments call for making competition law compliance part of corporate philosophy and the overall corporate governance framework of the businesses in India.

Saket Sharma works as an Associate Fellow in CUTS Institute for Regulation & Competition (CIRC). His work area includes managing research, conducting training programmes, pursuing research and lecturing in areas related to competition law, intellectual property law and the interface between these two laws. He can be reached at [email protected]

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved