or

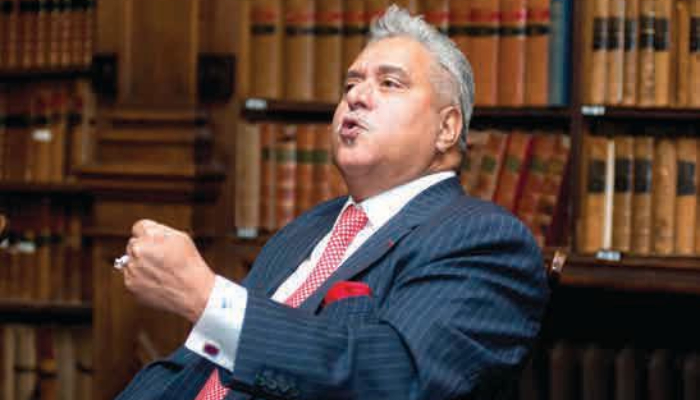

The process of extradition in the case of Vijay Mallya has started. He will soon be appearing before the court in London for his next hearing. What laws govern the extradition and does India have a fair chance of extraditing Mallya. Read out to know more.

When Vijay Mallya was arrested by the Scotland Yard in London on April 18, 2017, the State Minister of Finance, Santosh Gangwar, said to the media in India that Vijay Mallya would be brought back to India and the due process of law would be followed.

In London, the Scotland Yard announced to the media the Metropolitan Police’s arrest of a man on an extradition warrant. They said that a man (Vijay Mallya) was arrested by the Metropolitan Police’s Extradition Unit on behalf of the Indian authorities in relation to accusations of fraud. They told media the man, Mallya, was arrested after attending a central London police station and he would appear at Westminster Magistrates’ Court later that day.

Mallya did appear in the Magistrate’s court. But two hours later he walked out of the court with his lawyers. The Magistrate of the London Court granted him bail and Mallya tweeted after walking out: “Usual Indian media hype. Extradition hearing in court started today as expected.”

The former ‘king of good times’ is in the thick of corporate wrongdoing. He allegedly violated law with impunity. In an effort to save himself and his now-defunct company, his business dealings became murkier and his corporate misdeeds grew, and on March 2 2016, he fled India and took refuge in the United Kingdom.

Mallya has several cases against him from loan default to money laundering to bribing Indian government officials. He is wanted in several cases related to economic offences in India. Here is a brief summary of the cases in which he has been booked in India and issued non bailable warrants.

A consortium of 17 banks led by the State Bank of India has registered a case of loan default of ` 9000 crores. The loan has not been repaid since 2012. On March 8, 2016, the consortium of banks moved the Supreme Court to stop Mallya from leaving the country before repaying the loan.

For allegedly sending abroad a sum of ` 900 crore from his company, a case under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) has been filed by the Enforcement Directorate in 2016.

In July 2015 the CBI filed a case against Mallya and officials of IDBI bank. It was alleged that the banks had sanctioned loans far above the permissible limit and had foregone protocol.

In 2016, the Serious Frauds Investigation Office (SFIO) found that 17 Indian companies took loans from banks for financing the defunct Kingfisher Airlines. SIFO has accused Kingfisher Airlines of corporate misgovernance and issued notices to 17 companies and asked them to reveal the source of their funds.

The Revenue department has accused the Kingfisher Airlines of failing to deposit the service tax collected on ticket sales with the department and diverting the money for other purposes.

In March 2016 a non bailable warrant was issued by a local Hyderabad court against Mallya for allegedly dishonouring a Rs. 50 lakh cheque to GMR Hyderabad International Airport Ltd.

In July 2016 a Mumbai court issued another non bailable warrant against Mallya under applications filed by the Airports Authority of India (AAI). The report filed by the AAI stated that Kingfisher airlines had dishonoured two cheques worth Rs. 100 crores

India had asked Britain to extradite Mallya to face trial in India. He has nine nonbailable warrants issued against him by special investigative courts and magistrates court in India in relation to various alleged violations of law.

Extradition is a process of seeking return of a fugitive person from one country to the other country in order to stand trial or to serve a sentence in the country. ‘Fugitive Criminal’ means a person who is accused or convicted of an extradition offence within the jurisdiction of a foreign State and includes a person who, while in India, conspires, attempts to commit or incites or participates as an accomplice in the commission of an extradition offence in a foreign State

The Extradition Act 1962 provides India’s legislative basis for extradition. The Act consolidated the law relating to the extradition of fugitive criminals from India to foreign states. It was substantially amended by Act 66 of 1993

Sec 2. d. “Extradition treaty means a treaty or agreement made by India with a foreign State relating to the extradition of fugitive criminal and includes any treaty or agreement relating to the extradition of fugitive criminals made before the 15th day of August, 1947, which extends to, and is binding on, India;

(f) “Fugitive criminal” means an individual who is accused or convicted of an extradition offence within the jurisdiction of a foreign State of commonwealth country and is, or suspected to be, in some part of India.

A request for extradition can be initiated against a fugitive criminal, who is formally accused of, charged with, or convicted of an extradition offence. The Government of India has entered into bilateral extradition Treaties with 37 countries to bring speed and efficiency to the process of extradition. Besides, India has entered into extradition arrangements with 9 more countries

In May 2011, the Indian Government ratified two UN Conventions – the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (UNCTOC) and its three protocols.

Article 16 of UNCTOC can be used as a basis for extradition of fugitive criminals accused/convicted of offences that are classified as Organized Crimes. While ratifying the Convention, Government of India declared that “In pursuance of Article 16, paragraph 5(a) of the Convention, the Government of India shall apply the Convention as the legal basis for cooperation on extradition with other States Parties to the Convention. Indian Law Enforcement Agencies can seek to make use of the provisions of the convention accordingly.

The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), Government of India, is the Central Authority for all incoming and outgoing requests for Extradition. CPV Division handles extradition matters in the Ministry of External Affairs.

Extradition requests are sent to the Ministry of External Affairs for consideration by:

1.The State Government under whose territorial jurisdiction the alleged offence took place; 2. The Court of Law by whom the fugitive criminal located abroad is wanted; 3. Ministry of Home Affairs in respect of cases put together by investigating agencies (e.g. CBI, NIA etc.).

In urgent cases, when it is believed that a fugitive criminal located in a particular jurisdiction may flee that jurisdiction, India may request provisional arrest of the fugitive, pending presentation of the formal extradition request.

A request for provisional arrest may be transmitted through diplomatic channels, through the CPV Division of the Ministry of External Affairs. The facilities of the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) may also be used to transmit such a request, through the National Central Bureau of India, CBI, New Delhi.

Extradition offence means:

As per Article 2 of the India-UK Extradition Treaty, an extradition offence for the purposes of this Treaty is constituted by conduct which under the laws of each Contracting State is punishable by a term of imprisonment for a period of at least one year. An offence may be an extradition offence notwithstanding that it relates to taxation or revenue or is one of a purely fiscal character.

India and the UK have an Extradition Treaty in force since 1993. In February this year, a new round of dialogue on matters related to Extradition and Mutual Legal Assistance was held between the officials of India and the UK in New Delhi. According to MEA, the meeting was held pursuant to the decision taken during the visit of the UK Prime Minister to India in November 2016 wherein the two leaders had directed that the officials dealing with extradition matters from both sides should meet at the earliest to develop better understanding of each countries’ legal processes and requirements; share best practices, and identify the causes of delays and expedite pending requests so that fugitives and criminals should not be allowed to escape the law. However, as on date there is no proposal to seek modification in the extradition treaty between India and UK.

The extradition process has to follow these steps:

Extradition request is made to the Secretary of State, then the Secretary of State decides whether to certify the request. The Judge decides whether to issue a warrant for arrest and if the person wanted is arrested and brought before the court, he will be subjected to a preliminary hearing. Then the extradition hearing will start and then Secretary of State will decide whether to order extradition

Requesting states are advised to submit an initial draft request to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) or, in the case of Scotland, to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) extradition team, so that any potential problems can be resolved.

When an extradition request is made to the International Criminality unit (ICU) at the Home Office, the request will be valid if extradition is stated to be for the purpose of prosecuting or punishing a person accused or convicted of an offence in a category 2 territory( includes India) , and if the request is made by an appropriate authority on behalf of that territory. Where these basic criteria are fulfilled the Secretary of State certifies the request and sends it to the courts. Where the person is believed to be in Scotland, Scottish Ministers certify the request.

If the court is satisfied that enough information has been supplied, an arrest warrant can be issued. The court must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the conduct described in the request is an extradition offence (which includes the requirement for dual criminality). Generally the information accompanying a request needs to include:

After the person has been arrested, he is brought before the court and the judge sets a date for the extradition hearing.

The judge must be satisfied that the conduct amounts to an extradition offence (dual criminality), none of the bars to extradition apply, where applicable, there is prima facie evidence of guilt (in accusation cases), and whether extradition would breach the person’s human rights.

If the judge is satisfied that all of the procedural requirements are met, and that none of the statutory bars to extradition apply, he or she must send the case to the Secretary of State for a decision to be taken on whether to order extradition.

The judge’s decision whether to send a case to the Secretary of State can be appealed. The requested person can ask for permission to appeal the judge’s decision to send the case to the Secretary of State. Any application for permission must be made to the High Court, within 14 days of the date of the judge’s decision. However the High Court will not hear the appeal unless and until the Secretary of State orders the requested person’s extradition (see below).

If the District Judge orders the requested persons discharge, the requesting state can ask the High Court for permission to appeal that decision. Again, any application for permission to appeal must be made within 14 days of the judge’s order. If the High Court grants permission it will go on to consider the appeal. If the High Court allows the appeal, it will quash the order discharging the requested person and send the case back to the District Judge for a fresh decision to be taken.

The Secretary of State must order extradition unless the surrender of a person is prohibited by certain statutory provisions in the 2003 Act. The requested person may make any representations as to why they should not be extradited within 4 weeks of the case being sent to the Secretary of State. The Secretary of State is not required to consider any representations received after the expiry of the 4 week period.

Extradition is prohibited by statute in certain cases and if none of these prohibitions apply, the Secretary of State must order extradition. Or, if surrender is prohibited, the person must be discharged. The Secretary of State has to make a decision within 2 months of the day the case is sent, otherwise the person may apply to be discharged. However, the Secretary of State can apply to the High Court for an extension of the decision date. More than one extension can be sought if necessary

Appeal is only possible with the leave (permission) of the High Court. Notice of application for leave to appeal must be sought within 14 days of extradition being ordered by the Secretary of State or discharge being ordered by the Secretary of State. Any appeal by the requested person against the decision of the judge to send the case to the Secretary of State will be heard at the same time as the appeal against the Secretary of State’s order, assuming permission is granted.

A requested person, or a requesting State, can apply for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court against the High Court’s decision. Notice of application for leave to appeal must be given within 14 days of the High Court decision. Permission can be granted either by the High Court or by the Supreme Court itself. Appeals to the Supreme Court can only be made if the High Court has certified that the case involves a point of law of general public importance.

Unless there is an appeal, a requested person must be extradited within 28 days of the Secretary of State’s decision to order extradition (subject to any appeal).

Bars to extradition

A person’s extradition to a category 2 territory is barred by reason of the rule against double jeopardy if (and only if) it appears that he would be entitled to be discharged under any rule of law relating to previous acquittal or conviction if he were charged with the extradition offence in the part of the United Kingdom where the judge exercises his jurisdiction.

A person’s extradition to a category 2 territory is barred by reason of extraneous considerations if (and only if) it appears that— (a) the request for his extradition (though purporting to be made on account of the extradition offence) is in fact made for the purpose of prosecuting or punishing him on account of his race, religion, nationality, gender, sexual orientation or political opinions, or (b) if extradited he might be prejudiced at his trial or punished, detained or restricted in his personal liberty by reason of his race, religion, nationality, gender, sexual orientation or political opinions.

A person’s extradition to a category 2 territory is barred by reason of the passage of time if (and only if) it appears that it would be unjust or oppressive to extradite him by reason of the passage of time since he is alleged to have committed the extradition offence or since he is alleged to have become unlawfully at large (as the case may be).

(1) A person’s extradition to a country is barred by reason of hostage taking considerations if (and only if) the territory is a party to the Hostage taking Convention and it appears that— (a) if extradited he might be prejudiced at his trial because communication between him and the appropriate authorities would not be possible, and (b) the act or omission constituting the extradition offence also constitutes an offence under section 1 of the Taking of Hostages Act 1982 (c. 28) or an attempt to commit such an offence. If the judge decides the question in subsection (1) in the negative he must order the person’s discharge

Talking to a foreign press in London, Vijay Mallya has said that there is no ground for his extradition. He said that he was safe in this country under U.K. laws, until proven otherwise. “The government-owned banks are trying to hold me personally responsible for the failure of India’s largest airline and to repay their debts,” Mallya said.

“I have a counter claim on them as well. That is in the judicial system right now. Recovery of loans made to a PLC is a purely civil matter. The Central Bureau of Investigation, at the behest of the government, converted it into a criminal matter. And then charges of defrauding banks and money-laundering appeared,” he said.

“I will be and am severely contesting all this, legally. I firmly believe they have absolutely no case against me whatsoever,” said Mallya to the foreign press.

According to experts, India needs to show a prima facie evidential case against Mallya. The courts in London will also look at the case on the grounds of their own extradition Act. As explained above, there are many provisions in the Extradition Act 2013 which bar extradition and Mallya will have enough opportunities in the UK to challenge India’s extradition request on different grounds. It has been reported in the media that some extradition cases have collapsed when evidence against the defendant fell short of the standard of dual criminality. The court in London will also look at the angle of fair trial and prejudice while deciding the extradition of Mallya.

India has a dismal record of extradition. According to Gen. (DR) V. K. Singh (RETD), Minister of State, Ministry of External Affairs, in the last five years, only one fugitive criminal namely Samirbhai Vinubhai Patel has been extradited from the UK. The extradition requests in respect of criminal fugitives namely Raymond Varley, Ravi Shankaran, Velu Boopalan, Ajay Prasad Khaitan, Virendra Kumar Rastogi and Anand Kumar Jain have been rejected by the UK government.

As on March 2017, a total of 10 extradition requests made by India in respect of fugitive criminals namely Rajesh Kapoor, Tiger Hanif, Atul Singh, Raj Kumar Patel, Jatinder Kumar Angurala, Asha Rani Angurala, Sanjeev Kumar Chawla, Shaik Sadiq, Ashok Malik and Vijay Vittal Mallya are pending with the UK Government. The Minister informed the Parliament in March this year that the government was making diplomatic efforts for the extradition of criminals and economic offenders including Vijay Mallya.

“In case of Vijay Mallya, the Government of India formally had requested the Government of the United Kingdom on 8 February 2017 to extradite him and the UK Government had sent the extradition request to the concerned court in UK to initiate judicial proceedings against him,” the Minister said.

According to the latest report, on May 5 2017, the Indian government asked the UK government to cut unnecessary delays and impediments in the extradition of the fugitives, including Vijay Mallya. They say India doesn’t want to give any opportunity to the fugitives to circumvent the extradition process.

The process of extradition in the case of Vijay Mallya has started. He will soon be appearing before the court in London for his next hearing. He is going to fight the legal battle with all resources available to him. One has to see whether the long arm of the law catches him or he is smart and resourceful enough to prove all claims of the Indian government false.

The LW Bureau is a seasoned mix of legal correspondents, authors and analysts who bring together a very well researched set of articles for your mighty readership. These articles are not necessarily the views of the Bureau itself but prove to be thought provoking and lead to discussions amongst all of us. Have an interesting read through.

Lex Witness Bureau

Lex Witness Bureau

For over 10 years, since its inception in 2009 as a monthly, Lex Witness has become India’s most credible platform for the legal luminaries to opine, comment and share their views. more...

Connect Us:

The Grand Masters - A Corporate Counsel Legal Best Practices Summit Series

www.grandmasters.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Real Estate & Construction Legal Summit

www.rcls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Information Technology Legal Summit

www.itlegalsummit.com | 8 Years & Counting

The Banking & Finance Legal Summit

www.bfls.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Media, Advertising and Entertainment Legal Summit

www.maels.in | 8 Years & Counting

The Pharma Legal & Compliance Summit

www.plcs.co.in | 8 Years & Counting

We at Lex Witness strategically assist firms in reaching out to the relevant audience sets through various knowledge sharing initiatives. Here are some more info decks for you to know us better.

Copyright © 2020 Lex Witness - India's 1st Magazine on Legal & Corporate Affairs Rights of Admission Reserved